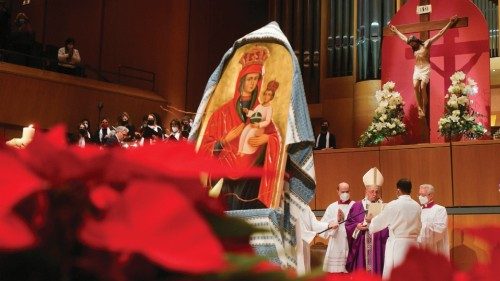

On Sunday afternoon, 5 December, the second Sunday in Advent, after returning from Lesvos, the Holy Father presided at Holy Mass in Athens’ Megaron Concert Hall. About 2,000 Catholic faithful participated in the Eucharistic celebration, some from the main rooms while others joined by video link from adjacent rooms. The following is the English text of his homily.

On this second Sunday of Advent, the word of God sets before us the figure of Saint John the Baptist. The Gospel highlights two important things: the place where John appears, which is the desert, and the content of his message, which is conversion. Desert and conversion. Today’s Gospel emphasizes these two words in such a way as to make us realize that they both concern us directly. Let us consider each of them closely.

The desert. The evangelist Luke introduces the scene in a particular way. He speaks of the solemn circumstances and the great men of that time, mentioning the fifteenth year of the Emperor Tiberius, the governor Pontius Pilate, King Herod and other contemporary political leaders. He then refers to the religious leaders, Annas and Caiaphas, who were serving in the Temple of Jerusalem (cf. Lk 3:1-2). At this point, Luke tells us: “The word of God came to John the son of Zechariah in the wilderness” (3:2). But how did that word come? We might have expected God’s word to be spoken to one of the distinguished personages just mentioned. Instead, a subtle irony emerges between the lines of the Gospel: from the upper echelons of the powerful, suddenly we shift to the desert, to an unknown, solitary man. God surprises us. His ways surprise us, for they differ from our human expectations; they do not reflect the power and grandeur that we associate with him. Indeed, the Lord likes best what is small and lowly. Redemption did not begin in Jerusalem, Athens or Rome, but in the desert. This paradoxical approach tells us something beautiful: that being powerful, well-educated or famous is no guarantee of pleasing God, for those things could actually lead to pride and to rejecting him. Instead, we need to be interiorly poor, even as the desert is poor.

Let us think more deeply about the paradox of the desert. John the Baptist — the Precursor — prepares the coming of Christ in this inaccessible, inhospitable and dangerous place. Usually, those who wish to make an important announcement go to impressive places, where they can be readily seen and address great crowds. John, on the other hand, preaches in the desert. Precisely there, in an arid, empty waste, stretching as far as the eye can see, the glory of the Lord was revealed. As the Scriptures prophesied (cf. Is 40:3-4), God changes the desert into a sea, parched ground into springs of water (cf. Is 41:18). Here is yet another heartening message: then as now, God turns his gaze to wherever sadness and loneliness abound. We can experience this in our own lives: as long as we bask in success or think only of ourselves, the Lord is often unable to reach us; but especially in times of trial, he does. He comes to us in difficult situations; he fills our inner emptiness that makes room for him; he visits our existential deserts. The Lord visits us there.

Dear brothers and sisters, in our lives as individuals or nations, there will always be times when we feel that we are in the midst of a desert. Yet it is precisely there that the Lord makes his presence felt. Indeed, he is often welcomed not by the self-satisfied, but by those who feel helpless or inadequate. And he comes with words of closeness, compassion and tenderness: “Do not fear, for I am with you, do not be afraid, for I am your God; I will strengthen you, I will help you” (Is 41:10). By preaching in the desert, John assures us that the Lord comes to set us free and to revive us in situations that seem irredeemable, hopeless, with no way out; he comes there. There is no place that God will not visit. Today we rejoice to see him choose the desert, to see him reach out with love to our littleness and to refresh our arid spirits. So, dear friends, do not fear littleness, since it is not about being small and few in number, but about being open to God and to others. And do not fear situations of dryness, because God is never afraid to visit us there!

Let us move on to the second word, which is conversion. The Baptist preached this insistently and forcefully (cf. Lk 3:7). This word too can be “uncomfortable”, for just as the desert is not the first place we would consider going to, so the summons to conversion is certainly not the first word we would like to hear. Talk of conversion can depress us; it can seem hard to reconcile with the Gospel of joy. Yet that is only the case if we think of conversion simply in terms of our own striving for moral perfection, as if that were something we could achieve as the result of our own effort. Therein lies the problem: we think everything is up to us. This is not good, for it leads to spiritual sadness and frustration. For we want to be converted, to become better, to overcome our faults and to change, but we realize that we are not fully capable of this, and, for all our good intentions, we constantly stumble and fall. We have the same experience as Saint Paul, who in these very lands wrote: “I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do” (Rom 7:18-19). If by ourselves, then, we are unable to do the good we would like, what does it mean for us to be converted?

Here your beautiful Greek language can help us by reminding us of the etymology of the verb “to convert”, metanoen, used in the Gospel. Composed of the preposition metá, which here means “beyond”, and the verb noéin, “to think”, it tells us that to convert is to “think beyond”, to go beyond our usual ways of thinking, beyond our habitual worldview. All those ways of thinking that reduce everything to ourselves, to our belief in our own self-sufficiency. Or those self-centred ways of thinking marked by rigidity and paralyzing fear, by the temptation to say “we have always done it this way, why change?”, by the idea that the deserts of life are places of death rather than places of God’s presence.

By calling us to conversion, John urges us to go “beyond” where we presently are; to go beyond what our instincts tell us and our thoughts register, for reality is much greater than that. It is much greater than our instincts or thoughts. The reality is that God is greater. To be converted, then, means not listening to the things that stifle hope, to those who keep telling us that nothing ever changes in life, the pessimists of all time. It means refusing to believe that we are destined to sink into the mire of mediocrity. It means not surrendering to our inner fears, which surface especially at times of trial in order to discourage us and tell us that we will not make it, that everything has gone wrong and that becoming saints is not for us. That is not the case, because God is always present. We have to trust him, for he is our beyond, our strength. Everything changes when we give first place to the Lord. That is what conversion is! As far as Christ is concerned, we need only open the door and let him enter in and work his wonders. Just as the desert and the preaching of John were all it took for Christ to come into the world. The Lord asks for nothing more.

Let us ask for the grace to believe that with God things really do change, that he will banish our fears, heal our wounds, turn our arid places into springs of water. Let us ask for the grace of hope, since hope revives our faith and rekindles our charity. It is for this hope that the deserts of today’s world are thirsting.

As our being together here renews us in the hope and joy of Jesus, and I rejoice in being in your midst, let us now ask Holy Mary our Mother to help us become, like her, witnesses of hope and sowers of joy all around us, for hope, dear brothers and sisters, never disappoints. Not only now, when we are all happy to be together, but every day, in whatever deserts we may dwell, for it is there, by God’s grace, that our life is called to be converted. There, in the multiplicity of existential or environmental deserts, there life is called to flourish. May the Lord give us the grace and courage to accept this truth.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti