The use of images in worship and devotions

In 2013, Steven Hrotic, a professor at the University of Vermont, made headlines for having organised an innovative course on the relationship between religion and science fiction. In fact, with a rich bibliography to support it, he considered how the authors of twentieth-century science fiction - from Isaac Asimov’s Cycle of Foundations to Frank Herbert’s Dune - had focused on the role that religion would play in the societies of the future on several occasions.

The results were surprising. In many works, in fact, religious institutions often played a salvific role, orienting the choices of men and women of the coming centuries. The most problematic aspects were mainly related to the age-old relationship between science and faith. Those interested in the topic can read in English the essay Religion in Science Fiction, published by Hrotic himself in 2016.

If we set aside utopias and dystopias, narrow the field to Catholicism, and make the Vermont professor’s suggestions our own, one might ask how and in what terms will the Christian faith be experienced in the next century. Obviously, a certain caution is needed to predict which direction the representation of the sacred, of holiness and bliss will take. However, the past and the present can help us to understand the future.

Santi in posa [Saints Posing], an insightful volume published by Viella, studies and analyses the use of photography in the processes of promoting the cult of saints and in devotional practice to date. Within the essay, edited by Tommaso Caliò, various experts in the field have analysed the influence that images have had on the canonisation of Maria Goretti, in the cult of Padre Pio, in the most diverse hagiographies or in the representation of the pontiffs of the 19th and 20th centuries.

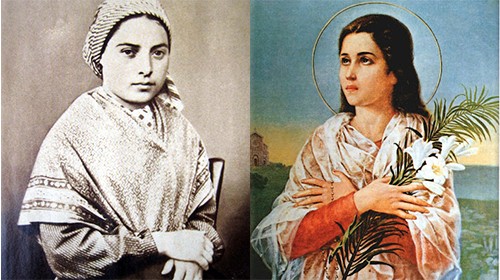

The “martyr of chastity” Maria Goretti - Caliò points out in the introduction to the book - probably did not have the opportunity to pose in front of a camera while she was alive. The absence of a face to propose to the faithful led, along with a vain search for portraits, to the adoption in the 1950s of the figure of her cinematic alter ego, the little protagonist of the film Il cielo sulla palude [The Sky over the Marsh], who, for her mother and her murderer, at that time an integral part of the promotional machine, resembled Maria “both in face and soul”.

The operation carried out on Bernadette Soubirous, the saint of Lourdes, is also interesting. Real photo books exist of her, even though she did not like posing, just as she did not like her image to be commercialised. In his book, Alessandro Di Marco reports a revealing episode of her intolerance. During one of the sessions she had in the studio of photographer Paul Dufour, when she was told to change her clothes “to be more beautiful”, Bernadette replied: “If Mr Dufour wants me to be in the photo, then let him be satisfied with my clothes, I won’t wear an extra brooch to look more elegant”.

Projecting us into the more or less near future, the big question mark, in a liquid society such as ours, in an age so conditioned by the reproducibility and sharing of images, is inextricably linked to the role that technology will play in this process of representation and self-representation of holiness and bliss. Clearly, this process must take into account both the communicative and the more strictly devotional aspects.

Pasquale Palmieri, a historian at the University of Naples who is very attentive to these issues, is sceptical about this. “I don’t believe in technological determinism”, he told Women Church World. “Having the possibility to use platforms, tools and devices does not mean that these are used effectively. Behind social networks, for example, there are real people who have needs, fears, desires, aspirations, and anxieties linked to the everyday and the supernatural”.

Palmieri is the author of the valuable La santa, i miracoli e la rivoluzione. Una storia di politica e devozione [The Saint, the Miracles and the Revolution. A history of Politics and Devotion], published by Il Mulino on the figure of Teresa Margherita Redi, a young Carmelite who died in Florence in 1770, aged just 22, was made a saint in 1934. He is very clear on this point; “Religious communication has always been a mediation between prescriptions and impositions that came from above and impulses and drives that came from below. Today, social networks satisfy a strong need for participation among the faithful, with an increasingly interactive sharing of holiness. Those who believe feel themselves to be protagonists in a devout practice. However, in devotion, there is a tangible aspect that must always be considered”.

Streams of communication are always finding new ways. We just have to think of a very recent editorial operation that is bringing hand-painted sculptures of saints and blesseds to newsstands, which can be bought for a few euros. These range from Saint Francis to Saint Rita, via Saint Clare, Saint Rocco, Saint Anne and Saint Nicholas of Bari. Then, if we open our Whatsapp to check our statuses and chats, we see how the images of Padre Pio, the Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ have been manipulated.

These are examples that lead us to reflect on two aspects. On the one hand the concreteness, the tangibility, the static nature of the figures of the saint and the blessed, which never fails even in these fast and temporary times like ours; on the other hand, the speed and ease of production, reproduction and sharing of images from one device to another.

by Alessandro Buttitta

Teacher and writer, author of “Consigli di classe” [Class Councils] and “L’isola di Caronte” [The Island of Charon], both by Laurana Editore.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti