The sisters chose

A silent rebellion at the origins of religious Congregations

Anno Domini 1566: with a solemn document in the form of a papal bull, Pope Pius V ordered the extinction of all female religious groups who refused to take solemn vows and withdraw into strictly cloistered communities. This was the last step in a long process that had seen a succession of alternating phases and opinions, and which provoked lively discussions between canonists and theologians.

At the heart of it all was a fundamental question, that of the freedom of religious women to act tangibly in the century through a social apostolate, and evangelising activity and preaching.

During the middle Ages and the early modern age, women’s religious experience had been expressed in a plurality of different forms and vows, which were not limited to the choice of a monastic-contemplative life only. The result was a lively and composite world, made up of women who moved independently in the society that surrounded them, sometimes managing to carve out real leadership roles as theologians, preachers and writers, and often of great profoundness.

In the 16th century, when faced with the explosion of the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church reacted by increasing controls on religious life and reducing the roles and powers of women, who were increasingly subject to male ecclesiastical authority. This took place in a climate of renewed suspicion towards women, who were weak, in need of constant protection and therefore destined only to the binary choice of marriage or monastery; and no possibility of following a “third state”. Consequently, first the Council of Trent and then by subsequent popes who specified that all “religious” women had to take solemn vows and established an indissoluble link between these and the observance of the cloistered institution. Simple vowed communities were free not to adhere to the obligation, but could no longer accept novices so therefore effectively condemned to extinction.

Thus, there ceased to be any possibility of being both mulieres religiosae and women free to live out their vocation actively during this century. At least in theory the matter was closed once and for all. The doors of the communities were bolted and the key thrown away. In this way - perhaps the high ecclesiastical hierarchies thought - the brisk and (in their eyes) dangerous female industriousness was finally tamed, appeased, channeled within an exclusively contemplative, well-defined and controllable religious and spiritual model, namely that of the cloistered nun.

Placated? Tamed? Not by a long shot. The ways of the Lord are infinite, and infinite are also the enterprising ways which women are capable of when they firmly believe in an ideal, in a mission to be accomplished, in a task to be carried out for the benefit and service of a few or of many. However, realising that an outspoken rebellion against the conciliar and papal decisions would be futile, these women religious were resourceful. They found alternative ways to remain on the front line, fighting ignorance and evil, bringing relief to the material and spiritual wounds of their neighbour, healing, evangelising, and educating.

While trying not to appear overtly rebellious, they did in fact rebel. They did so by making a compromise in their agreement not to be recognised as religious but as “semi-religious”, sisters who renounced their solemn vows, which was a deeply painful decision. Instead, they took simple or private vows, or in some cases no vows at all, and limited themselves to a promise of perseverance or stability in the life they had chosen. They did, however, adopt rules, and then establish a hierarchical organisation, which was usually headed by a superior general. This was followed by obtaining the recognition of the local diocesan authorities, who understood the importance of their action in the territory, not only for the people but also among the people.

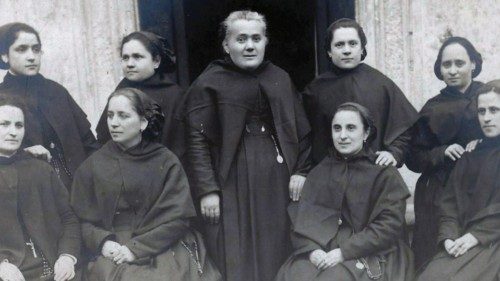

At the beginning, there were only a few groups of brave women, but from the second half of the 17th century onwards, they became more and more numerous and multiplied exponentially throughout the 19th century. The examples are numerous and varied. Starting with Mary Ward’s pioneering attempt, which was destined to fail because of the historical context in which it arose and the strenuous desire to maintain solemn vows. Then we move on to the Ursulines without seclusion (initially protected by prelates such as Carlo Borromeo and Agostino Valier), the pious teachers, the Medea nuns, the missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and so on. Pages upon pages would not be sufficient to mention them all. Tenacious and resolute, they remained firm in the conviction that, eventually, even the Roman Curia would understand the important mission entrusted to them by God to build a better society.

Therefore, they were rebels but prophetic at the same time. Although the Church struggled for a long time to give them an official position, it finally understood and formally recognised them at the end of the nineteenth century, after some tentative opening up in the eighteenth century. Of course, it all took about three centuries. Centuries in which thousands of women devoted themselves to caring for the sick and the marginalised, to recovering runaway women, to missionary work and to educating girls. Indeed, with their educational commitment aimed at girls from every social class (and no longer just aristocrats, educated at home or in expensive monastic convents) they demonstrated a sensitivity and awareness of the problem of female education that was ahead of its time. Once again, therefore, they were not only rebels but also prophetic and decidedly avant-garde.

These women became the protagonists of their own destiny. They taught and still teach others to take (or take back) their lives, to be persevering, to believe in Providence, to build a worthy future in line with their talents received at birth. Today, women’s religious congregations continue to be an important reality and one of the pillars of Catholicism throughout the world.

An army of hard-working women, rooted in the resourcefulness and determination of some early, indomitable, silent rebels.

By Alessia Lirosi

Associate Professor of Modern History, Niccolò Cusano University

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti