Pilar Bellosillo contributed to changing the Church, and not only in Spain

“Women wonder why the liberating power of the Gospel has, throughout history, been so conditioned and contained. And why Jesus’ attitude towards women and all the oppressed, a truly revolutionary attitude in his day, so significant and luminous, has lost its force and meaning over the centuries”.

In the 1960s, Pilar Bellosillo asked herself these questions -which continue to be relevant today-, and committed herself with the Church and in the Church to fight with hope and tenacity for the liberation of women. This liberation of the oppressed, commenced with the profound conviction that Christ liberates, liberates women, liberates those who suffer any form of oppression that conditions and blocks the realisation of the original dignity and equality of all people.

The “signs of the times”

Pilar was a prophetic and charismatic woman, like the prophets Deborah and Hulda in Israel, a “messenger of God” in the 20th century. She lived from 1913 to 2003, a historical phase marked by key events in the history of humanity such as the two world wars; the civil war in Spain; Franco’s regime; national Catholicism; the first democratic elections; and, in the Church the Second Vatican Council. An infinity of “signs of the times” to which Pilar was attentive and to which she tried to respond.

She was born in Madrid in 1913, and from an early age, she showed herself to be a free and responsible person, whose definition of utopia was a more humane, more just, more liveable and more fraternal society. At the end of the Spanish Civil War, she committed herself to the apostolate, which she described as an exciting personal adventure that would last a lifetime. Like the prophets mentioned above, Pilar considered herself a servant to the Word, she was captivated by it, and to which she was prepared to devote her life. She was not content to passively accept the biblical texts; instead, she integrated them into her search for truth and was particularly attentive to what the Word says about women. She made her own particular exegesis at a time when the inferiority of women compared to men and their specific roles in the Church and the world were justified with theological and scriptural arguments. Together, with a group of Christian women from different Countries, they became aware of what they described as a “permanent ambiguity (or rather contradiction) in the Church: the evangelical principle of the absolute equality of the sexes is affirmed at the level of supernatural life but inequality is justified at the practical and disciplinary level”. They committed themselves “to helping the Church from within in this critical awareness, in order to stimulate her to respond to God’s designs for the human being: man-woman”. The creativity and reflections of these women have had a great impact on the foundation of thinking about women, in both the civil and religious spheres; however, in the 1950s it was a titanic task to bring about a change in mentality that this implied.

An example of Christian leadership

Pilar’s life was one of unconditional love and service to God and the Church. Commencing with lay ecclesial institutions, she took on many responsibilities, and which she helped to renew by promoting social commitment and work for justice. When she was just 27 years old, she was appointed national president of the young people of the Acción Católica Española (ACE) and later, as national president of the women of ACE, she set up the Family Formation Centres (Catholic Centres of Popular Culture), the Impact Formation Week, and the Campaign Against Hunger - Manos Unidas. In 1952, she joined the international council of the World Union of Catholic Women’s Organisations (WUCWO), of which she was appointed president in 1961.

Council: Personal Pentecost

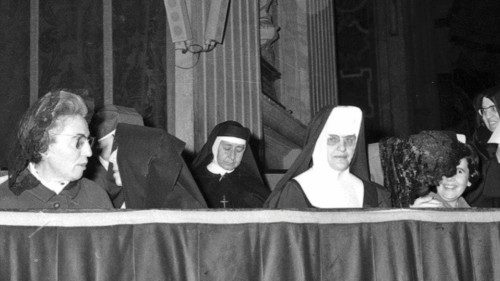

Pilar Bellosillo was the only Spanish laywoman to attend the Second Vatican Council. She experienced that phase intensely; in fact, the most important event of her life, and which she sums up in a sentence, when she said, “This great Pentecost of the Church was my personal Pentecost, and how well I understood what the vocation of the laity in the Church was!”.

Her prophetic mission, like that of Jeremiah, was not a call to immobility, to preserve what was already there. In an age characterised by crises and need for renewal of the world and the Church in which Pilar lived, God would pronounce an important word that did not fit into old clichés. Pilar discovered this call at the Second Vatican Council and wrote:

“I remember spending nights in vigil, which I described as ‘troubled by the Spirit’, in which I put order into the great quantity of things we received. This sometimes required of me a painful stripping away of what does not remain and always the joyful acceptance of the new. When the themes were presented, we were told, “So far the tradition of the Church and this is the new”. This required me to make an effort to integrate the new into my inner being and to make an effort to be consistent. Sometimes this process was very painful, but exciting.

Pilar was part of the commission that prepared Gaudium et spes. Her contribution, together with that of the lay auditors at the Council, was fundamental in relation to the importance and responsibility of the laity in the Church; the need to achieve equality for women in the Church and society; the importance of private initiative in the Church (international Catholic organisations); and, the ecumenical dimension. These were all areas to which Pilar committed herself throughout her life with an avant-garde, anticipatory and precursor spirit.

Ecumenism presupposed for Pilar the fact of experiencing the culture of encounter and social friendship that Pope Francis speaks of today. Catholic and Protestant women have experienced ecumenical encounters based on profound friendship, and in ecumenism friendship, states Pilar, is something fundamental.

Critical fidelity

The difficulties she encountered in putting the council’s statements into practice and the resistance of the hierarchy to consistently implement its conclusions -especially regarding the role of women in the Church-, meant that Pilar was very disappointed as a believer and as a person. However, she never stopped trusting in Christ’s Church. She spoke of difficult, even “dramatic” times, but it never occurred to her to abandon the Church or to take a passive attitude in the face of difficulties. She continued to work for ecumenism and participated in the Spanish political moment and its transition to democracy, while working in every field to obtain a just, Christian-inspired democracy.

The cause of beatification

Pilar and her companions in ACE and WUCWO worked within a utopist horizon, aware that “time is superior to space”, working for the long term, without being obsessed with immediate results, while patiently enduring difficult and adverse situations (see Evangelii gaudium 222 and 223). In this way, they carried out a true revolution of ideas. They became aware that women were the protagonists of that moment in history, characterised by the awakening of female consciousness in the world, and that it was the time of their “liberation”. They were convinced that their initiatives could have a historical mission to fulfill for the future in the Church. They promoted the organisations to which they belonged, so that they would be increasingly consistent with their mission, in line with the progressive evolution of society and the Church, while putting into practice the socio-community dimension of the Church and promoting the creation of networks and links between organisations.

In 2019, in the Archdiocese of Madrid, the phase preceding the opening of the cause of beatification was initiated. We can say that she is one of the women who contributed most to the transformation of the Church in the 20th century, and an example of Christian leadership. In Pope Francis’ pontificate, some of her prophetic insights are being promoted, for example, social friendship, ecumenism and interreligious dialogue, the openness of the Church to the role of women within it, and the importance of what we now know as the path to synodality.

By Adela González

Manos Unidas, development cooperation NGO of the Spanish Catholic Church

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti