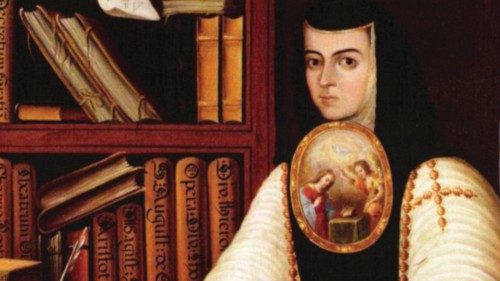

Juana de la Cruz’s challenge

Today, when people talk about Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz, it is not uncommon for them to readily disassociate her from the Catholic Church. This is because the secular world cannot explain how, with a genius such as hers, already on a par with the western classics; she could have been a faithful daughter of the Church. In order to dissociate Sister Juana from Catholicism, there are those who have put forward the easy argument that she was only Catholic because in the 17th century she could not have been anything else. There are those who are assured that her rebellion was such that, in order to escape male slavery, she made the least oppressive choice for a woman of that time, that of life in a convent. However, the incontrovertible fact is, and will continue to be, that Sister Juana was only possible because she was Catholic. To remove the term Catholicism from the formula that results in Sister Juana would be like removing the oxygen atom from the water molecule.

To claim that Sister Juana was Catholic only because she was born in New Spain in 1648, i.e. because circumstances gave her no other possibility, is not sufficient to refute that the identity of the nun from Nepantla was profoundly Catholic. If it was at all impossible for Sister Juana not to be Catholic, then her existence becomes impossible too. Both her confessor, Father Núñez de Miranda, and her biographer, the Jesuit Diego Calleja, inform us that this was in fact the case. In her Protesta de la fe, Sister Juana states:

“I affirm that I believe in Almighty God, three distinct persons, and one true God. I believe that the Word was incarnate and became man in order to redeem us, with all the other things that the Holy Mother Roman Catholic Church believes and professes, of which I am an obedient daughter, and as such I desire, and declare to live and die in this faith and belief”.

In fact, if one looks closely at that period of history, the inseparability of Sister Juana from the Catholicism of New Spain makes sense. Unlike in Countries with a Protestant tradition, the female figure has always constituted a paradox in markedly Catholic Countries. While the social sphere was governed by men and for men, the family and spiritual spheres were undoubtedly dominated by the mother figure. This is evident in the family context of little Juana de Asbaje (or Azuaje, as the documentation states). It was her mother, Isabel Ramírez de Çantillana, who governed the domestic enviroment and supported her offspring. Her mother Isabel was an independent woman as she described herself in her will. “I was an unmarried woman and I had as natural daughters Donna Josefa María and Donna María de Azuaje and mother Juana (Inés) de la Cruz, a nun from the convent of Saint Jerome in Mexico City”.

In the predominantly Catholic Hispanic world, there have been very important women writers such as Sr Juana. To name just a few: Santa Teresa de Ávila, Úrsula de Jesús in Peru, Sister María de Ágreda, Marcela de San Félix, Sister Ana de la Trinidad, Luisa Carvajal y Mendoza, María de Zayas, Ana Caro de Mallén, María de Guevara, Cristobalina Fernández de Alarcón, Ana de Castro Egas, Francisca Josefa del Castillo

However, we should not think that women enjoyed complete freedom to develop as intellectuals and literate women. It is well known that men constantly resorted to various arguments to prevent women from developing as thinkers. The very fact that men complained about this helps us realise that, in fact, there were women who did so.

Here we are talking in particular about the querella de las mujeres, an intellectual debate between misogynists and - to use a similar term - philogynists. It is important to emphasise here that all philogynist treatises present theological arguments in defence of the female gender. It is also good to remember that the theology that could be written in the Hispanic world was that which had been authorised by the Catholic Church. Therefore, based on a language and logic that predates Catholicism, women were defended as much as they were repudiated.

Once again Catholicism reappears here as an ambit of possibility. About this debate, Sister Juana disputes the fact that men in the Church order women to keep silent, stating “I would like St Paul’s interpreters and commentators to explain to me how they understand the verse Mulieres in Ecclesia taceant (1 Corinthians 14:34), silence your women in the churches”.

A few lines later, Sister Juana explains how this statement should be understood by saying, “And in another verse: Mulier in silentio discat (1 Timothy 2, 11), (let the woman learn in silence), this verse being more in favour than against women, since it orders women to learn and to learn it is clear that they must keep silent. And it is also written: Audi Israel, et tace [listen to Israel and be silent] where all men and women are spoken of and all are commanded to be silent, because for he who listens and learns it is right that he should listen and be silent”.

In the same Respuesta a sor Filotea, [in which she replies to the bishop of Puebla who in a book written under the pseudonym Filotea urged her to leave her studies aside] when Sister Juana spoke of her ability to write and think, she says that the Church “by her most holy authority does not forbid me, why should others forbid me?”.

It is not a question here of erasing Sister Juana’s feminine rebellion in order to place it in the context of Catholicism, but of understanding Catholicism from the point of view of rebellion. Moreover, this takes on enormous importance when we contemplate the theology developed by Sister Juana.

For example, let us take her poem Sueño. In its 975 lines, Sister Juana devotes herself to describing a dream, “It was night, I fell asleep, I dreamt that I wanted to understand at once all the things of which the universe is composed. I did not succeed, not even in distinguishing by categories; not even a single individual; disappointed, it dawned and I woke up”. Sister Juana brings together three Catholic theological currents. Scholasticism, which is expressed in its recourse to categories in order to understand the universe; Neoplatonism, which is expressed in the theme of the soul’s journey that seeks to understand the totality; Hermeticism, which appears with the recurring theme of the dream, that is, the oneiric realm and its dimension of profound knowledge. Sister Juana challenges theology to integrate three divergent currents.

Even if other elements could be added, such as her masterly theological treatise - the Carta Atenagórica -, the general idea seems clear. Rebellion and shades of heterodoxy characterise Sister Juana, but they must be considered perfectly Catholic. Sister Juana was haughty, rebellious, creative, and seductive precisely because she was Catholic.

By María Luisa Aspe Armella

Researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies (CEID), Mexico; member of the Academic Committee of the Latin American Academy of Catholic Leaders

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti