Three women give a name back to the Mediterranean castaways

“The boy is dead, one way or another he is dead, and that is enough for her to go and see him”. So begins the book Uomini e caporali. Viaggio tra i nuovi schiavi nelle campagne del Sud [Men and Corporals. A Journey among the New Slaves in the Southern Countryside] by Alessandro Leogrande. A great writer and intellectual, who has dedicated his entire short life “in defense of the lowly and the fiercely exploited in the most diverse contexts”, as his father wrote when announcing his sudden death two years ago.

The boy was a foreigner working in the fields. A truck ran him over, rendering him unrecognisable. He is buried in a cemetery in the heart of the Tavoliere delle Puglie. There is a cross indicating the burial place with the words UNKNOWN written in block letters.

“Incoronata is obsessed with the fact that one can die without being known, and without being mourned”. Therefore, this old labourer, wrapped in her inseparable shawl, has adopted the gesture of dividing flowers between her husband’s grave and that bare cross. Then, she decided to have a tomb built with the date of death, a short prayer, the image of a Madonna and, at the top, the word IGNOTO in bronze letters, as if it were an actual name. From these gestures, a physiognomy slowly emerges, a name, Miroslaw, a nationality, Polish, an existence, a history of exploitation and violence. Something that is a memory.

“A person is truly dead when no one remembers him or her anymore”, writes Bertold Brecht.

And from the damned oblivion of the unburied without identity come the soldiers of the Great War in Abel Grance’s beautiful film J’accuse (1919). Zombies that denounce the inhumanity of war and the condition of those who are just one among thousands of indistinct corpses on a battlefield of which the living have lost memory. As if to say, relegating the dead to the no-man’s-land of pitiless indifference makes them zombies, spectres that eventually terrorize our consciences that have become accustomed to oblivion.

The Mediterranean, July 2016. “In the hold we found a layer of biological material 80-90 centimeters high lying along the entire 23 meters of the ship. It was people”. This is how the chief engineer of the fire brigade described his descent into the depths to recover the 1,000 castaways trapped in the Egyptian fishing boat that sank in the Sicilian Channel a year earlier, on 18 April 2015. This is how the most frightening migration tragedies is recounted. A tangle of human tissue, clothes and objects. Nothing else was left. To try to give a name to the dead before burying them was “a civilized duty”, explains Cristina Cattaneo, Professor of Forensic Medicine at Milan’s Statale University. Professor Cattaneo was one of the anatomical pathologists who searched for people's physiognomies among that indistinct “biological material”. Three months of work at the NATO base in Melilli, Sicily. From her meticulous anatomies emerged the report card with the average mark of ten sewn into the jacket of the boy from Mali or Mauritania; the corner of a shirt knotted with a red string where another boy kept a small handful of his own land. In those fragments of identity taken away from the indistinct there is, in short, that common humanity made up of aspirations, hopes, and painful detachments in which to recognise oneself. You are like me. I am like you. This massacre -of which there may remain no traces-, is a barbarity that concerns us both. On the other hand, the thousands of unconsoled and anonymous Covid-19 deaths from the pandemic have forced us to experience at firsthand what it means to end up in a daily “death toll”.

The link between women and caring for the dead is also evoked sarcastically but with unquestionable truth in a passage from James Joyce’s Ulysses. “A task befitting them”, thinks the protagonist Mr. Bloom, as a corollary to the pains of giving birth.

I myself have very often seen, at least here in the south, women’s familiarity in dealing with death, the body to be composed in a pose that would give dignity, closing the eyes, softening the expression on the face, the putting on of the good dress. A way of opposing transfiguration and, in an extreme gesture, preserving the trait that identifies, and makes us recognisable. A form of pietas for the dead, and for the living who mourn them.

It is always a woman, the researcher Giorgia Mirto, who, since 2011, has been travelling to cemeteries and civil registry offices looking for traces of the thousands of shipwreck victims buried in various towns in southern Italy and Sardinia. She is keen to say that hers “is not a mere calculation […] I make sure that people know what has happened, that something of that person may survive death itself, at least in the memory of loved ones”. These words are all the more necessary if we think of how families, who are exhausted by the search for their loved ones, have finally decided to adopt any grave.

Observing Giorgia Mirto wandering around in ‘Campo 220’ of Palermo’s Rotoli cemetery, where there is an air of abandonment and seeing her bend over the squares of paper protected by cellophane and write down the few details in a notebook is like participating in a secular prayer.

The same spiritual charge is required by a work of art such as Salāt by artist Emanuele Lo Cascio, created for the 2012 Più a Sud project. A stele of black reflecting marble innervated by waves reproduces exactly a fragment of the sea of Lampedusa. The dimensions are the same as the Muslim prayer rug. Why? “The sculpture asks the observer for a moment of concentration, of reflection in solitude, of respectful prayer. The sea in its depths is always calm, silent, meditative, a holder of mysteries, of life and death. This fragment of the sea, agitated on the surface, creator of desperate shipwrecks but also of hope and salvation, conceals this in its invisible depths”.

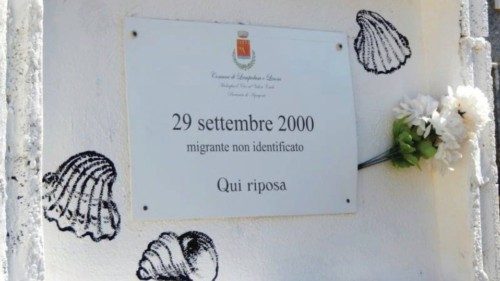

From the invisible depths of this carpet of sea and meditation, there have been many victims of the humanitarian catastrophe that this island has witnessed since the second half of the 1990s. They have found not only a burial on Lampedusa, but also a gesture against “dehumanization”. The 13 bodies buried in a handkerchief sized plot in 1996 or 1997 were buried by the cemetery caretaker, who took care to place crosses over the burials. To those who challenged his decision, he replied with that intelligent humanity of the humble, “For me, putting up the crosses was like saying we are all the same”. This story is told to me by Paola La Rosa (a volunteer at the Ibby Library and member of the Lampedusa Solidale Forum) who in 2003, decided to come and live on the island, and has been opposing “the entire reception system, based on a logic that presupposes the dehumanisation and depersonalisation of individuals, which is all the more deplorable when applied to the dead”. Defenseless of the defenseless, I think to the dead, the nameless dead, and myself.

Therefore, with the Lampedusa Solidale Forum, it has always welcomed the rescued to the Favaloro pier with some hot tea, and wrapped the survivors in warm blankets. It has opposed the obscenity of the plaques ordered by the mayor Bernardino De Rubeis in 2011 when at least 50,000 people arrived in Lampedusa. An annus horribilis with shipwrecks and heavy human costs. Those plaques can now be seen unused in some corner of the cemetery: IMMIGRANT UNIDENTIFIED OF MALE SEX AFRICAN ETHNICITY BLACK COLOR.

The Forum and the work of Paola La Rosa are responsible for the names (Ezechiel, Yassin, Ester Ada, Welela, of whom there is also a photo sent by her brother), the dates, the circumstances of the shipwrecks or of the discoveries, fragments of stories, and even details such as the “four interminable days” in which the Turkish merchant ship Pinar with the lifeless body of Ester Ada was left at sea before it was allowed to land. In 2009, four days of detention off the coast was already scandalous. This is why the cemetery is an essential stopping point for anyone who wants to understand the drama of migration. Even the writer and artist Armin Grader in 2018, who arrived in Lampedusa for a volunteer project, made his pilgrimage with Paola La Rosa and felt the need to “humanize” those graves and their slender stories, decorating the tombstones with marine drawings, such as fish, islands, seagulls, shells, starfish. This is a beautiful gift.

The funeral of Yusuf Ali Kanneh, the six-month-old baby who left Guinea with his mother and died in the shipwreck off Libya on 11 November 2020, is heartbreaking. They raise a difficult question: how can we make the memory become a shared memory in some way? A shawl, like Kornati's shawl, provides the answer. During the funeral, a Lampedusa woman instinctively wraps a crocheted shawl around Yusuf's mother, who is very young, 18 years old. And what is a crocheted shawl?

It is a world of weaving, of gratuitousness, of beauty that has never been elevated to the dignity of art precisely because it is linked to the female domestic world. Crocheting is one of the few gestures made by women within the walls of their homes that are not ephemeral, it is a moment in which they work together, to create a community.

Hence the idea of creating a repository of memory through stories and crochet work. A handmade square and a personal memory that you want to save from oblivion to be sent to the Lampedusa Solidale Forum as a gesture of affiliation to an international community that recognises itself in the values of the individual. Launching the project on social networks and then receiving thousands of crocheted tiles together with private stories (from Italy, Germany, France, and Peru) happened in an instant. Thus, “Yusuf's blanket” was commenced. Many squares sewn together to evoke this ideal community scattered around the world that wants to leave a sign of memory, to weave a different story based on care, a historically feminine but inclusive gesture. Many men have also joined in. A way of being in the world.

“Our idea was that there should be a plot made up of individual stories which, through the weft of the plot, would create a unique story”, explains Paola La Rosa.

The first place where the 11 blankets already sewn will be taken will be the grave of little Yusuf. Places of memory, on the other hand, also serve to remind us of who we have become, not just who we have been, explains historian Pierre Nora.

Thus, Lampedusa, the Mediterranean, the Balkan route, all the places where this humanitarian catastrophe has been taking place for decades, put our civilization to the test: they tell us precisely who we have become.

Lastly, if every time a story is told, these thin stories destined for oblivion, we return to giving dignity and life to existences, then this very article of mine wants to be, in its own way, a form of resurrection.

by Evelina Santangelo

The author

Writer and editor.

For Einaudi Evelina Santangelo has published the short stories L’occhio cieco del mondo [The Blind Eye Of The World] for which she received the Berto and Mondello awards, and several novels, including: Senzaterra [Landless], and Da un altro mondo [From Another World] which was book of the year for Fahrenheit Rai-radio 3, in 2018; Superpremio Sciascia). Again for Einaudi, she edited Terra matta [Mad Earth] by Vincenzo Rabito, translated Firmino by Sam Savage and Rock 'n' Roll by Tom Stoppard. Her articles have appeared in national newspapers, blogs and weeklies.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti