The life of Zeinab Alif, from Sudan to Italy

A story from a century ago that speaks to us today

There are five places in Zeinab Alif’s life: the first, the Kordofan region of Sudan where she was born and grew up until the age of eight. The second, Cairo in Egypt where she was sold into slavery. The third, Rome where she arrived after being ransomed and where she met the Pope. The forth, Belvedere Ostrense near Ancona where she was baptised and entered the Poor Clare boarding school, and finally Serra de’Conti, in the province of Ancona too, where I met her for this interview.

In 2017, I had just started gathering ideas for a new novel. I wanted it to be set it in Serra de’ Conti, my grandmother’s hometown, where my mother spent most of her summer holidays during childhood and adolescence. My intention was to follow in the footsteps of my great-grandfather, an anarchist, Nicola Ugolini, who lived there but disappeared and left Italy after his wife’s death in Spain. However, I found few traces of this great-grandfather, for though my mother had not met or know much about him, she did remember a venerated nun in the village, who had lived many years earlier in the convent of Santa Maddalena.

I had not started out with the idea of writing about a nun’s life, but I became curious, for it seemed incredible to find saints and anarchists living in the same place.

The monastery has not been there for many years, instead, in its place there is a Museum of Monastic Arts. The caretaker asked us if we were there for the Moretta, and I nodded, lying, because I still did not know who she was. The theatrical tour recounted the life of the nuns over the centuries. There were trunks containing lace, jugs full of cocoa powder, spices tucked away in the cupboard, letters sent and received, and little drawers of what had once been the dowry cupboard. There was a whole women’s world locked away in that basement.

I bought all the books and booklets for sale, and was struck by one in particular, written by Graziano Pesenti. On the cover, there was an image of a black nun who was holding out her hands, this was she, this was Zeinab Alif.

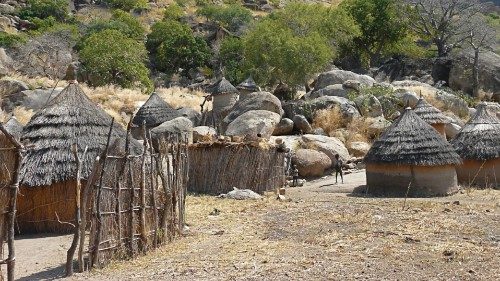

The first important date in Zeinab’s life is 1885 when she was taken from the Nuba Mountains in Sudan, where she lived in a stone house. Her house was different from the others in the village, which had red, circular walls and a thatched roof. Her father was the head of the village and grew cotton, sesame, millet and sugar cane. One afternoon while her mother was absent, and the nanny went outside for a moment, leaving the children alone, Zeinab and one of her little brothers were kidnapped by Arab raiders. They were taken into the desert, then up the Nile. Zeinab was eight years old and knew nothing about the world. Taken to Cairo in Egypt, she is exhibited naked for whoever wants to buy her. Zeinab cannot read or write, does not even remember her mother’s name, and she does not know how to return home.

A year later, Zeinab found herself serving in a man’s house, airing his rooms and cleaning his hookah. One day, however, she notices in front of the window a man in a long black tunic, who is going in and out of houses, talking to children. So, she plucks up courage and approaches him. The priest asks her in Arabic if she wanted to go away with him, that he would teach her to read and write and take her far away, Zeinab accepts.

This was the Genoese priest, Nicolò Olivieri, a citizen of the Kingdom of Sardinia and Piedmont, who, with his own money or that of his friends, ransomed enslaved girls and boys to take them to Italy and relocate them to the various religious institutes. He is the founder of the Pia Opera di Riscatto. The price for ransoming a girl is 400 lire. In his letters, Nicolò says that the girls are sold as mares, like lambs.

After a long negotiation, Zeinab’s price was settled at 350 Italian lira. The girl left her master’s house, who says behind her as she leaves, “an African girl outside of Africa will not live long”. Fortunately, he was wrong, for Zeinab’s life is only just beginning. The little girl, on whose life he had put a price as if she were poultry, is to become blissful.

This was Zeinab’s first boat trip, and to be her last. The sea is stormy and the girls below deck fear another misfortune. Their journey to Italy is not so easy, taking seven months to complete. At sea, Zeinab begins to learn Italian, and Nicolò tells her about Jesus and Mary, and about the Bible. They dock in Marseilles and proceed from there in slow stages, because at that time there was no railroad that led directly to Rome. Zeinab is untamable, and plays pranks and pinches her travelling companions and does not let them sleep. Her stubborn, curious, shrewish character is beginning to show.

From Rome, Zeinab was sent to Le Marche region to be educated.

On April 2, 1856, she entered the boarding school of the Poor Clares at Belvedere in Jesi, but felt lonely and lost without Nicolò and the girls who had travelled with her. In addition, she felt different from the other boarders, for she does not speak their language well and the food is poor and tasteless. For the first time she think of running away, but in the end she gives up on that. Her coming closer to the faith begins here, when her plans to run away are put aside and her gaze rests on what she can learn, and music opens her ears to something sacred.

Zeinab asked for her First Communion, receiving it adorned with silver embroidery. She chose her own name too, and is transformed, leaving behind her the fears and the beatings and becomes the future Sister Maria Giuseppina Benvenuti. When she does so she asks Jesus to make her his bride, a saint.

Her spirit, however, does not change, and she describes herself as “fiery”, as ardent. There is one thing that makes her incandescent more than anything else does and that was playing music. She sings so well, but wants to play the organ more so. From the initial lessons, it is clear to everyone that this is her instrument. Every Sunday people come to hear her play, and her mission becomes to attract people to church to listen to her music.

She has not become a nun yet. Many years have passed, but religious orders cannot accept novices, and the clash between Church and State is alive and strong. Maria Giuseppina could choose whether to follow a career as an organist, return to Sudan or wait and insist on entering a convent. She decided not to give up and in 1874, thanks to the direct intervention of the Pope, she entered the convent as a chorister, having already received a solid education in Latin, literature and music.

Twenty years later, in 1894, there were just seven nuns left in the San Domenico monastery. Among them, there is Sister Maria Giuseppina, and as the youngest, she has to take care of the others, who are prostrated from the lack of food and old age. The bishop of Senigallia decided to unite them with others in the Serra de’ Conti monastery, and this is how Moretta arrived in the town where my great-grandfather lived.

When the abbess of the monastery died in 1909, everyone clamoured for Sister Maria Giuseppina to take her place. Thus, she become the guardian of a small group of women who were about to confront illness and the war years together.

During her two terms as abbess, Sister Marie-Josephine helped the other nuns to find suitable work, avoided making them fast if she saw they were too thin, and took on simple tasks such as at the porter’s lodge.

The bond between her and her community is such that in 1914, when the sisters were asked to leave Serra, the people revolted by throwing stones at the bishop’s men who had come to take them away. On the threshold of war, she won the tug-of-war that had been waged for years with the bishop not to deprive the village of such an important place of worship.

Her final years were tormented, Maria Giuseppina gradually lost her sight, but she never stopped praying and performing her rituals, such as taking water from the well every morning. As she pulled on the rope to raise the full bucket, she always says, “Lord, save the souls in Purgatory as many as the number of drops that I am pulling up”.

It has been 700 years since St Francis died, and Mary Josephine has fallen. She has hurt herself badly, and the wound does not heal. Her memory lapses. There are moments when she lacks lucidity, she has little time left.

One of the nuns asked her to give a sign when Paradise arrived and Sr Maria Josephine agreed. To the last, she tried to recover, to play, but on the evening of April 24, 1926, she died.

In the morning, at five fifteen, her body is cold, but three bells peel in the monastery. It is Zeinab, she has just announced that she has arrived in Paradise, that she has finished her journey.

By Giulia Caminito

The author

Giulia Caminito, born in Rome 33 years ago, made her debut with the novel La Grande A [The Big A] (Giunti 2016), which won the Bagutta opera prima, Giuseppe Berto and Brancati Giovani awards. In 2019, she published Un giorno verrà [A day will come] (Bompiani), which won the Fiesole Narrativa Under 40 award. Her latest novel is L'acqua del lago non è mai dolce [Lake water is never sweet] (Bompiani 2021). As editor, she is in charge of Italian fiction for the Giulio Perrone publishing house, and on the editorial staff of Letterate Magazine. She curates Under - a festival of new writing with the Associazione Da Sud, held in schools in Rome.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti