A strong, authoritative, unsubmissive woman: An historical analysis

In May 2011, Ave Mary, Michela Murgia's book, was published and was a huge success with the public. The writer highlighted with ruthless lucidity how the image of the Virgin has been exhibited over the centuries as a model of modesty and submission for women, and encouraged to endure sacrifices and violence. This was not the first time criticism like this has been voiced. The philosopher, Simone de Beauvoir, in her 1949 book The Second Sex, had considered how Mary represented the “defeat of women” because she presented a mother who “kneels before her son, freely acknowledging her own inferiority”. A few years later, the anthropologist Ida Magli, along the same polemical lines, highlighted the cultural construction of the Marian myth in her study La Madonna. The symbolic figure of Mary is a product of the male imagination -often celebrated above Christ himself-, exalted by the celibate clergy as the incarnation of the feminine, and becomes functional to the patriarchal context of Christian society, which had instead marginalized women.

These criticisms, which have often been provocative, highlighted the manipulations of how the Mother of Jesus has been represented, and which have weighed heavily on the formation of women. Indeed, Mary’s “yes” (Luke 1:38) has traditionally been interpreted and proposed by the great preachers and spiritual fathers as a model of modesty for Christian women. In Our Lady, they saw the silent and welcoming figure par excellence, the paradigmatic image of femininity. The Virgin had thus become a prototype of humble acceptance not only for consecrated women, who were called upon to endure all mortifications, but also for laywomen, who were indoctrinated in the ordinary catechesis of parishes as children; and, as adults, in the secrecy of the confessional as well as in homilies or other sermons to be assimilated while listening passively. Moreover, even the heartbreaking image of the Mother, crushed by the pain of the death of her Son, had become an icon of impotent suffering and human defeat.

Today, feminist theologians are aware of certain distorted and discriminatory aspects of this education and of an exaltation of Our Lady that has not led to a substantial change in women's roles in the Church. They wonder if she can still be considered an example for women, and represent in some way a new humanity that suffers and aspires to freedom, be seen as a “sister” in faith and struggle, a subject of emancipation and redemption, and, finally, if she can be a subject of formation for a new female identity.

First, it should be reconsidered that Mary is not a model to be pointed out only to women and, above all, she is not an icon of silent and passive acceptance; on the contrary, she is a witness of active faith and she is so for all believers. Luther, who had fought against the Marian cult’s deviations, which often degenerated into superstition, had written the Commentary on the Magnificat, considering the mother of Jesus as a model of Christian life, an object of God's pure grace, a disciple following Christ, a symbol of the Church, a mother and an educator. Even the Koran exalts her virtues, pointing to her as the true believer to whom we owe honor and respect, a spiritual reference point for all Muslims, and not only for women.

Second, we must recover the formative role she played in the life of Jesus. Today’s approach to the Jewishness of the family of Nazareth helps us to rediscover positively the figure of "Mary, the educator” who was instrumental in the development of Jesus’ personality. In the Jewish culture, the delicate task of religious education was also entrusted to the mother, for it was she who had a dominant place in the home, considered a small temple. It was she who had the task of sanctifying the family through the practice of precepts linked to the domestic liturgy and the ritualistic Sabbath with the lighting of lights, a sign of the gift of life and, therefore, of peace and joy. If Jesus is the harmonious, integrated and inclusive man we know, we owe it to his mother.

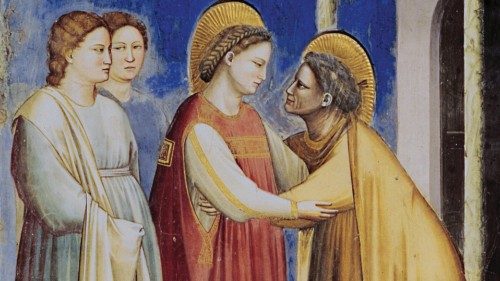

In addition, if we rely on the narrative of Luke’s Gospel, we must note that Mary appears to be an autonomous and courageous girl, a woman who is subordinate: she does not question her father, and she does not consult her husband, as would have seemed the thing to do at the time. Her “yes” is not a passive and submissive acceptance, but a response to God's plan, just as it was for Abraham (Gen 22:1), father in faith, and for Moses (Ex 3:4), liberator of the people. She is the protagonist, the prototype of the believer who entrusts himself to God's saving initiative. She is not a humbly submissive servant, but the Lord’s handmaid, that is, she who represents the people of Israel who remain faithful to God (Is 48:10-20; 49:3; Jer 46:27-28) and who impatiently await the fulfillment of the promise. In her, we recognize those who in the sacred text are defined as the poor of Israel (anawim), those who not only rely on God and his merciful arms, but who announce the overthrow of the logic of the world. In addition, it is this image of a strong woman that has taken hold in the spiritual experience of so many women who have been formed in the “school of Mary”; for example, as those religious of the monastery of St. Anne in Foligno. They wanted to represent Mary in a chair, portrayed in the Temple with the book of Scripture, seated on an authoritative seat, at the moment that she teaches, explains and announces the Word of God to the doctors of the law and the companions who meditate on the Bible with her. In this sixteenth century fresco, situated in the green cloister of the monastery, the educational dimension of Mary emerges strongly. In the context of a religious community of educated and literate Franciscan tertiaries called by the historian Jacques Dalarun a real “intellectual foyer” with an educational vocation, Mary teaches the doctors of the Temple as explained by the attentive study by Claudia Grieco, (Effatà 2019).

In the experience of women's religious history, Mary is essentially presented as an authoritatively active figure in the lives of believers. She is no longer a woman of ablative passivity, helpless in the face of pain; on the contrary, Mary is an attentive and compassionate mother, a woman who is close to the suffering of humanity so that pain might be transformed into life. Let us think for a moment of the many charitable or educational foundations, which have found inspiration in the figure of the Virgin; for example, the S. Maria del Popolo degli Incurabili hospital, founded in 1521 in Naples by Maria Longo, or the Compagnia di Maria Nostra Signora, founded by Jeanne de Lestonac in 1606 for the education of the girls of the people. It is impossible to list all the institutions linked to Mary. After all, it would be an arduous task to tie up the threads of an articulated and differentiated swarm of realities that traverse the world in all Catholic countries, and find in Mary inspirational reasons for life, faith and apostolate.

The Mother of Jesus, however, is also the authoritative woman who guides the fate of the Church to reform. This was true of Bridget of Sweden, Catherine of Siena and Domenica of Paradise, to name but a few. For these mystics and prophetesses, the Virgin -who questions every Christian about his or her actual readiness to be pliable in God's hands-, was not only an encouragement to walk the arduous paths of faith. In addition, she is the one who is the guarantor of the reform of the Church, which needs to be continually renewed in the light of Christ's message.

Therefore, Mary of Nazareth could be a model of formation for women today. In order to avoid falling into the traps that reduce her into a model of docile submission, and insofar as her image is reread with a different interpretive key, it can help to represent the instances of the new generations of women and their need for freedom and authority.

By Adriana Valerio

Historian and theologian, professor of History of Christianity and Churches at the University Federico II of Naples.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti