The culture of the biblical world distinguished a father and mother’s formative task toward their sons and daughters. Proverbs 1:8 assigns the Hebrew term mûsar to the paternal function of disciplining, correcting, and admonishing, while for the mother it uses the term torah, understood as instructing, and directing. Israelite wisdom advises shemà that is, to listen to, obey the mûsar, and not natash, that is to abandon, despise, renounce the torah.

As a concept, torah originated in pedagogical-feminine settings, and from such settings, mothers influenced, through the education of their children, the society of the time. Later, this distinctive term, which referred to maternal teaching, was reserved to designate God’s instructions to his people. The Church sees in Mary the highest expression of the “feminine genius”, which, starting from the pillars “love”, “obedience”, “humility” and “service”, participates in the integral formation of Christ, High and Eternal Priest. He, too, as Pope Francis says, did not come into the world as an adult, but small and fragile, “born of woman”, according to the sapiential prudence of the Kingdom. Intimacy with Jesus, from the silent years in Nazareth, is the basis of the Marian school, where He progressed “in wisdom, in stature and in grace”, guaranteeing His identity. When St Teresa of Calcutta preached to priests in the Vatican, she began by begging Our Lady for “her heart”, so that she could, from it, receive Jesus, love Him and serve Him in the painful guise of the poor. Mary offers women of all times “the mirror [...] of dispositions, attitudes, and gestures that God expects of them”, engaged in the presbyter sphere of teaching-learning (cf. Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Collaboration of Men and Women in the Church and in the World, May 31, 2004, no. 15). Here, I summarize these women's contributions by organizing them and placing emphasis on the four dimensions taken up by the new Ratio fundamentalis institutionis sacedotalis.

The Human Dimension

From the perspective of otherness, the Human Dimension benefits personal identity by fostering affective maturity. Interpersonal relationships between the sexes collaborate with synodal pastoral processes in majority-female contexts. Human formation spreads from the academic-cathedra classrooms, where science is supported by an integrative and personalized way of seeing, and by identifying each face with its name, its history and its process. Those who work in hidden spaces such as in the kitchen also contribute to this dimension, through informal conversations that are used to create a balance of emotional states. Blessed laywoman, Concepción Cabrera de Armida sums up a common concern when she urges bishops and trainers to examine the motivations of candidates for the priesthood carefully. She makes a plea that no one should ascend to the altar if the conditions are not fully fulfilled; therefore, she has described the demanding profile of those who wish to exercise this service.

The Spiritual Dimension

Commencing from a Catholic thinkers tradition, such as Saint Catherine of Siena, “ministers of the Blood of Christ” are exhorted to awaken their consciences, through knowledge of themselves and of Christ, through whose goodness they receive the Sacrament of Orders, in order to provide for the People of God. The Doctor of the Church of Siena corrected them with charity and firmness, demanding generosity and not avarice, which has a tendency to sell grace. Her spiritual director, Brother Raymond of Capua, who developed a contact with her, being, at the same time, her disciple. Saint Teresa of Jesus, allows us to identify theological spaces such as confessionals, conversations, and accompaniments, where important priests, influenced by women of honorable spiritual roots, strengthen their configuration with Christ.

The Intellectual Dimension

In Edith Stein’s wake, Dawn Eden Goldstein makes it clear that the contribution to the presbyter world made by female academics’ is not limited to the latter's socio-affective development, but also and above all includes their intellectual maturation. Such maturation is achieved, in my opinion, when, thanks to women's practicality, theoretical references and acquired skills flow into the service of ecclesial pastoral priorities. Therefore, the involvement of women in the initial and ongoing formation of the presbyter does not consist in preventing a biological maternal deficiency.

The Pastoral Dimension

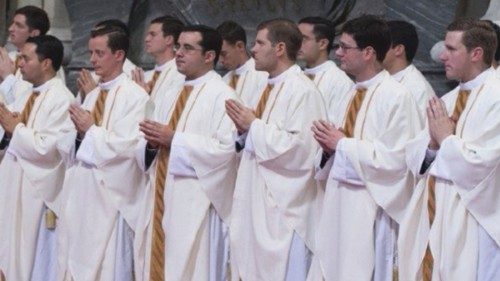

Pope Francis' teachings to priests are of great value. “Remember your mothers, your grandmothers, your catechists, who gave you the Word of God, the faith, the gift of faith! They have passed on to you this gift of faith” (Presbyteral Ordination Homily, April 21, 2013). This legacy from historical roots is combined with that of teachers of faith and science, increasingly present in seminaries and other academic and reflective spaces, filling roles of “teacher”, of “faithful”. Whether in sacramental homiletical settings or in any pastoral practice, we not infrequently realize that the good presbyter does not improvise; in his ministry, we are all present. Many priests, who are grateful for Marian care, do not end their day without paying homage to her with the Salve Regina.

By Santa Àngela Cabrera

OP, Dominican religious, professor of Sacred Scripture at the Pontifical Seminary of St. Thomas Aquinas and dean of the Faculty of Religious Sciences at the Catholic University of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti