The Venetian rebel forced

Arcangela Tarabotti, who spoke of equality in the seventeenth century

I will call her Elena; and, disrobe her of the monastic habit she never wanted to wear, at least for the duration of this article. This is the robe that she has struggled with all her life as if it were poisoned, like the dress that Medea had delivered as a wedding gift to Jason’s bride-to-be. This is what her words say, what we read in her writings, which have the strength, wit and even genius of a real writer. While reading L’inferno monacale [The nun’s Hell] by Elena Tarabotti I often thought about the diary of Etty Hillesum, written, from the opposite of pain. For Etty, too, was a curious young woman with a sparkling intelligence, condemned through no fault of her own, imprisoned in a senseless jail.

However, Etty Hillesum, in the little time she had, managed to take in the world; she loved, she walked around her city, she slept in different beds. Her body was available to her to enjoy or suffer with. In addition, of this harvest she kept the hunger, and that ability to see the beauty in anyone and in anything, which accompanied her until the end of her days, in the Auschwitz concentration camp. I thought of her because in her letters, and in her diary, Etty often writes that she would like to become a writer.

This is probably the same life that Elena Tarabotti had imagined for herself, if she had not been locked up in a convent against her will when she was only thirteen. From which she was never to leave again. She writes of the fate befalling the little girls like her, who were “incarcerated not in a holy and religious cloister, but in the bowels of the intended whale that never vomits them up”. Etty was Jewish, while Elena had inherited from her father a small physical defect, which are the reasons for their life imprisonment and death sentence. Etty Hillesum died when she was 29 years old, and did not write very much because she had no time, however, there is her diary and letters. As has often happened to other writers whose lives are short, for example, Raymond Radiguet, Alain Fournier, Emily Brontë, Sylvia Plath, we are left to regret the absence of wonders we will never read. Nevertheless, in the little she did write, she really was a writer, not someone who aspires to be one. As was the case with Elena Tarabotti, each within the limit they were given. For Elena, it was the walls that imprisoned her; and, she chose not to ignore them, they became the subject of all her writing. How could she have done otherwise? What could a woman who had been taken prisoner at the age of thirteen tell us if not about her imprisonment and despair?

Elena, Elena Cassandra Arcangela Tarabotti, was born in Venice in 1604, in the Castello district, to a wealthy family. However, the family’s wealth was not sufficient to provide adequate dowries to marry off the numerous daughters. Aut murus aut maritus. According to a custom of the time, her father Stefano chose to sacrifice the one who, according to his unquestionable opinion, would have had the most difficulty finding a husband. Elena was lame. Just like him.

We do not know anything else about her appearance. Her writings and essays about herself are always accompanied by a portrait that for a long time was believed to be of her. Instead, it is of Maria Salviati, wife of Giovanni de’ Medici and mother of Archduke Cosimo I, a work attributed to Pontormo and held in the Uffizi gallery in Florence. The painting was produced about fifty years before the birth of Elena, who is therefore not the portrayed woman with a long, thin nose, eyes slightly different from each other, the mouth well drawn.

Elena was lame, clubfooted, like the devil.

Could this really have been the reason why she was chosen as a victim of that abomination, of forced confinement in a monastery? Maybe, or perhaps she had a less submissive character than the other sisters, a vocation to independence that was read in her soul even if she was only a child. Perhaps Elena was identified as one of those difficult to tame females, dissatisfied, too intelligent to settle for a marriage of convenience. One of those hysterical women, whose passion or worse yet, reasoning could blow up the assembly line of procreation/inheritance/revenue. Besides being lame, perhaps Elena was not smart enough to hide her intelligence and talent, so the family had to work hard to cut them off.

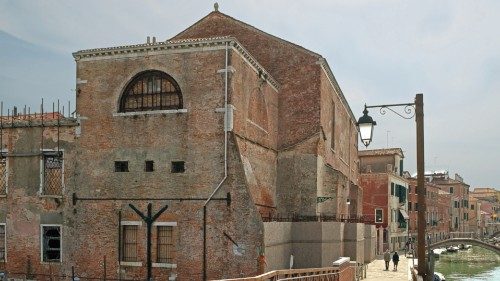

In 1617, at the age of thirteen, she was destined to the Saint Anne monastery. From that convent, where she was consecrated twelve years later, she never left.

The first book, entitled Tirannia Paterna [Paternal Tyranny], the one in which the anger of the condemnation was still fresh, Elena wrote when she was twenty years old but it was not published. It came out posthumously, under the pseudonym Galerana Baritotti and the title La semplicità ingannata [Deceived simplicity], and was put on the index of forbidden books in 1661. The book condemned the practice of being forced to become a nun, and claimed female dignity and the right to an education. The next one, L’inferno monacale, remained unpublished for four hundred years, but the manuscript circulated and a transcript survived in Alvise Giustiniani’s collection. The first edition dates back to 1990 (Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier), and was edited by Francesca Medioli. I bought a copy on the Amazon website, where it costs 1 euro and five cents; there it is, stubbornly. She is certainly not a famous writer, and yet, after 400 years, her book can be purchased on an e-commerce platform. Like one of those bacteria that hides amidst a mummies’ bandages to survive, and once freed, circulates boldly.

What is that hell? The grotesque version of the paradise to which they had promised to lead them. Everyone lies to the girls who must cross the threshold of the convent. The family lies when it promises them that they will live in a place where everything is playful and light, where they will be free from the obligation to have to work and fulfill the functions of a wife or mother. In the convent, they say, there will be plentiful food on which to feed and vague dwellings in which to rest. But above all, the girls who are forced to become nuns are told that they will be able to enjoy the utmost freedom.

As Tarabotti writes of the fathers who rid themselves of their daughters by imprisoning them, “Avaricious of little money, but prodigal of other people’s freedom.” They lie, as do the other women, those nuns, who are victims of this practice of confinement too. Indeed, the latter lie even more so, according to the psychological mechanism that we know about. In confinement, the most heinous are the companions of destiny, who through whistle blowing and deception try to obtain even a tiny exception from their restraint.

Inside, the young girls are dressed in a dark woolen robe, but dressing them in camel skins, would be preferred, just like the hermits, or even laurel leaves, to save money, or nothing at all, just their own body hair, to save even more. In fact, what happens is that families abandon their daughters, once they have become nuns. Whether it be because of feelings of guilt, or relief to have them off their hands, the family does not want to know anything more about them and above all, they do not want to spend anything more on them. Moreover, the convent is filled with fighting, and imprecations against the relatives who caused them that condition, and against the superiors who permitted it. As Tarabotti continues, “like furious beasts held in indissoluble knots, they desperately revolt and struggle within those walls, without retaining any other result than a tormenting grief. Obedience is only a function, a formal rite, everything else is vanity, like smoke and mirrors and shadow that deceives the eye of those who look at the skin without penetrating the marrow”.

The vow taking ceremony resembles a funeral. As she describes, she [the novice] is “thrown down on the ground, covered with a black cloth, and a candle is placed at her feet and one by her head, while litanies are sung over her. These are all signs that render her extinct. She hears her own funeral and she accompanies all this with tears and sobs from within the coffin, while sacrificing all her senses to passion and sorrow. The superior then gives her a veil, which is called a sorazzetto”, to remind her that the next three days she will have to be silent.

Dead, buried, and forgotten, Elena Tarabotti finally attained the publication of her fourth book, which is entitled, not by chance, Paradiso monacale [Nuns Paradise]. Yet it is not a retraction at all, but a more skillful exercise in fiction. “I cut off my hair, but I did not uproot the affections, I reformed my life, but the thoughts, that just like my hair, grow more and more, are increasing.” Just as she had written in L’Inferno, qui nescit fingere, nescit vivere.

Moreover, she wrote again, for she was always writing, which was published in 1644, in Venice with a publisher called Valvasense. The Antisatira was a response to the misogynist satire of the Sienese Francesco Buoninsegni Contro ’l lusso donnesco [Against the luxury of women]. The work was published with the initials (“D. A. T.”) and was dedicated to Vittoria Della Rovere, wife of the Grand Duke Ferdinando II, who was in correspondence with the author. In 1651, again with a pseudonym, this time Galerana Barcitotti, she published a polemical treatise Che le donne siano della spetie degli huomini [That women are of the species of men], written in response to a 1595 Latin work attributed to Valens Acidalius and printed in Italian in 1647.

In 1650, for the publisher Guerigli, Lettere familiari e di compliment was published. This volume detailed her network of relationships, friends, correspondents, especially with the Accademia degli Incogniti [Academy of the Unknowns]. The Academy’s members met in the home of its founder, the Venetian writer Giovan Francesco Loredan, where they held discussions, published works and organized performances.

Philosophically libertine, and suspected of Gnosticism, the Academy was dispersed in 1644, when Ferrante Pallavicino, one of its main organizers, was beheaded in Avignon for lese majesty and apostasy.

Sister Arcangela Tarabotti, on the other hand, died “of fever and catarrhal illness” on February 28, 1652 at the age of 48.

by Elena Stancanelli

The author

Elena Stancanelli was born in Florence and lives in Rome. She made her debut in 1998 with Benzina (Einaudi Stile libero); founded the Associazione Piccoli Maestri of which she is president; and, is a columnist with the Italian national newspapers, la Repubblica and La Stampa.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti