The liturgies of the Christmas season plunge us into the very heart of our Catholic faith. Christian piety, as expressed in our popular traditions, tends to dwell on the poetry and human drama of the Lord’s nativity. We set up a Christmas crib in our homes and we retell, especially to our children, the ancient yet ever new story of the Savior’s birth in poverty, the message of peace brought by the angels, and the visit of the Magi, who came from the ends of the earth to worship the newborn King.

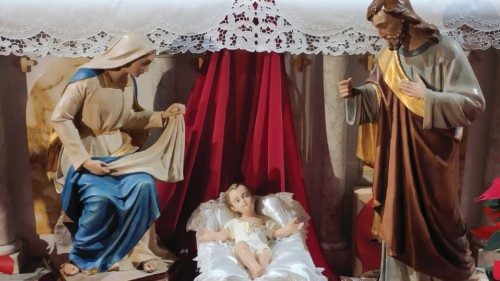

Here in Italy, it is a tradition for families, local artisans and parish churches to create elaborate and artistic nativity scenes. Those from Naples are famous for their scores of figures drawn from everyday life and set against a typically Italian landscape of ancient ruins, lively villages and striking natural beauty. Shepherds guard their flocks, innkeepers serve steaming plates of food, including spaghetti and pizza, to men playing cards, an open-air market is in full swing, children play, and washerwomen gossip around a public fountain. In a word, the whole scene is one of overwhelming life and activity. Usually the central figures in this drama, Our Lady, Saint Joseph and the baby Jesus are not easy to make out. Amid the bustle of daily life, they remain peacefully apart, alone with the Christ Child, seemingly unaffected by all that is taking place around them.

These crib scenes remind us the Son of God was born in hiddenness, while the world went its busy way. We are reminded that, like so many of the figures in the scene, we too can be oblivious to the mystery of grace present and at work in our midst, simply because we are caught up in so many infinitely less important things. We fail to make time, to open our eyes and to see the things that really matter.

The Church’s liturgy in the Christmas season has little to do with folklore. It dwells not so much on the story of Christmas, the colorful events surrounding the birth of the Messiah, as on its ultimate meaning, its cosmic significance. We see this already in the Mass of Christmas Day, whose readings center on the majestic prologue of John’s Gospel. Saint John, echoing the first words of the Book of Genesis, invites us to contemplate, not the beginning of creation and time, but the eternal begetting of the Son, the Word through whom all things were made. That Word, in the fullness of time, became flesh and dwelt among us, and gave us power to become children of God, sharers in the Father’s glory.

One line of the Prologue always struck me, from the time I was a child, when we would hear it each Sunday in what used to be called the Last Gospel. It reads: “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness did not overcome it”. No one who has glimpsed that light, however dimly, can fail to be moved by this verse. God’s light, his eternal life, dwells among us and no darkness in our own lives, or in our human history, can ever overcome it.

In a very real way, the three great mysteries that the liturgy commemorates in the days after Christmas are mysteries of light.

The first is that of Our Lady’s divine maternity, celebrated on January 1st, the Octave of Christmas. Among the many threads of which this great feast is woven is the Church’s veneration of Mary’s virginal conception and her perpetual virginity. Here in the West, the most evocative representations of these mysteries are found in the paintings that show Our Lady kneeling in prayer before her newborn Child, as the light of glory shines all about. With supreme discretion, the artistic tradition alludes to the hidden fulfillment of the prophecy and sign of the Virgin who gives birth. The image of Mary, Virgin and Mother, wrapped in light as she contemplates the Christ Child, is meant to invite us, with union with her, to contemplate the eternal generation of the Son from the Father — light from light, true God from true God — now mirrored in the human birth of her Son in time. And to see in his glory the fullness of light and life that awaits us in heaven, where we hope one day to see him face to face.

The second mystery of light celebrated in the Christmas season is, of course, the Epiphany. Here the emphasis of the liturgy is on the star whose light led the Magi, as representatives of the nations, to Christ, the Savior of the world. Saint John tells us that in the mystery of the Word made flesh, the light which enlightens every man and woman who comes into the world, has shone among us, full of grace and truth. The world was created in that light and can only find salvation by being drawn ever more fully into it. Only in that light can we understand the ultimate meaning of our life, our vocation and our destiny as individuals and as a human family. Epiphany reminds us that the Savior’s birth was the beginning of the Church’s mission to preach this Good News to people of every nation, race and tongue, until the very end of time. And to spread the Kingdom of justice, holiness and peace that Christ came to bring.

The final mystery of light we celebrate in this Christmas season is the Baptism of the Lord, which is itself the first of the five new “luminous mysteries” that Saint John Paul

In that movement upward, in union with the Son of God made man, we come to understand the deepest meaning of Christmas, the mysteries it celebrates, and their significance for our lives and for the redemption of our world.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti