Saints, lay people, nuns: all women devoted to solidarity

If there is a road for the salvation of Naples, it is a road made by women, by ancient tradition that has been erased, forgotten, and calumniated by the city itself. It was out of devotion that Maria Longo, who was later blessed, founded the Hospital of the Incurables in the Spanish Naples of the sixteenth century. Over the following centuries, the hospital was destined to become a beacon of European scientific research. However, in the first instance, it was intended for everyone, even the poor, a hospital for childbirth and insanity, a women’s hospital for women. There were even prostitutes taken from the street to assist doctors and surgeons.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, it was due to this devotion that Sister Ursula Benincasa put together a combative women’s group. This was despite the fact that the city was so hostile to women, and that they led the illiterate Ursula to torture, questioning and tormenting her, doubting her holiness. Like Saint Mary Frances of the Five Wounds, she had grown up amongst Spanish soldiers, amid violence, famine, epidemics and rape. Yet, many years after her death -and during the plague of 1656-, the viceroy obeyed her, and built the convent that today is one of the oldest universities in Italy.

Take a leap forward to the middle of the nineteenth century, it is another woman, Teresa Filangieri, the philanthropist and writer, and granddaughter of Gaetano Filangieri, the philosopher and jurist, and daughter of Carlo, general, that we owe, in Naples, the food banks when there was cholera and the first children’s hospital in Europe, the future Santobono.

Women are always on the front line and ahead of the times because they think and argue that everyone should be treated, even the poor, even children, that everyone needs the right answer.

In Naples, in the twentieth century, there is a long list of writers and women who were committed to combatting hunger and ignorance. From Matilde Serao, a journalist and publisher, who called for the recovery of the city, to Anna Maria Ortese, an important literature and ethics voice, who thanks to her dedication saw the closure of the scandalous Granili neighborhood. An area that caused a massacre due to its poverty and filth, and who wrote the unforgettable chapter of Il mare non bagna Napoli, which showed the disastrous housing conditions there to an Italy that was still fragile and short-sighted at the end of the war. Fabrizia Ramondino who, before becoming a writer, was involved in the foundation of the Proletarian Children’s Canteen, to the militant Professor Vera Lombardi, because, let us not forget, it is at school that consciences are formed.

Naples, where cholera, plague, the camorra clan or coronavirus, problems are never lacking, the women form a line, an address, a certainty, they often represent the best of a literary, philosophical and artistic flowering among the highest in the world.

And in this Covid-19 era, this has remained unchanged.

And, today, it was Anna Fusco, an artist and merchant, and who had inherited the oldest tobacconist’s license in Naples, in Piazza Trieste and Trento, in the heart of the historic center, who came forth. During the lockdown months, Anna, who also suffers from asthma and lung problems, picked up Teresa Filangeri’s mantel. It was she we recall who in a time of rampant cholera had led all the noblewomen of Naples to roll up the sleeves of their expensive clothes and cook in the street, because epidemics also come from hunger.

Anna cooks hot dishes with her whole family, and has replaced the closed city canteens. The homeless come to eat at her place, but also many people without a family or those who have no other support.

Anna was even featured in The New York Times for her ingenious and generous initiative.

To talk of it first, however, was another woman. Laura Guerra, who has always been committed to social issues, is a journalist on the Neapolitan editorial staff of Scarp’ de Tenis, a newspaper sold on the street partly written and distributed in many Italian cities by homeless people. Laura teaches writing in the center of her cooperative and during the lockdown she records distance learning lessons for a work which does not cease, indeed it intensifies in this city that has always experienced a complex, stratified emergency.

Laura reports on the work of Pina Tommasielli, a general practitioner, who offers free serological tests to teachers. He also who deals with prevention in suburban and difficult districts of the city, Soccavo and Pianura and highlights the fact that women take care of everything in the family, everyone elses diseases, their work and food, while often neglecting themselves. In the end, when they get sick, it is too late, and the engine of the house fails. An engine that neglects to take preventative steps in order to always think of others first.

Laura writes in her newspaper about Angela Parlato, a teacher with forty years experience, and an activist in many social centers. In Montesanto and in the Spanish Quarters (those of Saint Ursula Benincasa, the same of Saint Mary Frances of the Five Wounds, because the centuries have passed but the problems remain, although apparently changed) is responsible for bringing a basket of food to those who cannot do the shopping and delivery to those who cannot leave home.

And so she realizes that distance learning in the Bassi area, with its old blind and asphyxiated houses, built on the ground floor and facing directly onto the street, without a computer or connection, in families where a cell phone is divided into four, works worse than it already works badly for everyone. For this reason the Angela decides to act as a bridge between distance learning and the children of the houses where she goes to bring the shopping. Pasta, peeled tomatoes, gigabyte refills and photocopies: Angela Parlato’s basket has different consumables and needs.

After all, not having a connection in the alleys of Naples, between the walls of the sixteenth century, is easy.

Meanwhile, schools in southern Italy, in the hot autumn, are shaken by climate change every other day, whether it is sudden rains or sea whirlwinds (the “tropee”). They have reopened to the desperation of mothers, the panic of teachers and the very high economic and cultural cost, brought about by the pandemic. The consequences are already visible, a price that in Naples and the south is higher than elsewhere, which has affected businesses, retailers, hotels, theaters, cinemas, schools and universities, which has exposed the weakest.

A continual gigantic cultural emergency is therefore taking place once again in the city where the education of children has always been left to the women to resolve, as Matilde Serao, Anna Maria Ortese, Fabrizia Ramondino wrote and still today say, repeating, reporting on those of us who work closely with schools, with children of all ages, with teachers.

In the Sanità, a neighborhood famous for being the birthplace of Antonio de Curtis, aka Totò, and for some of the most enchanting baroque buildings in the city designed in the eighteenth century by the architect Ferdinando Sanfelice. Here, too are the terrible feuds between the Camorra and for the “stese”, shootings that often involve ordinary citizens and children, for years, yet Pina Conte, a teacher and entrepreneur, has been resisting for years. By committing all her family’s patrimony she has renovated an old building where they hold school for those who would not otherwise go to school, where they also study mandolin and music, where they learn to make costumes for the theater. From Pina Conte’s classrooms have emerged workers, professionals, artists who would have otherwise have gotten lost and ended up with a gun in their hands.

There are, in short, those who never stop, even in the oblivion of their commitment, like Sister Giuseppina Esposito, who for years has been active at the Binario della Solidarietà [Solidarity Track] in Gianturco. Gianturco is the neighborhood that goes unmentioned in her novels, but that readers around the world now encounter when reading Elena Ferrante, where the emergencies are ongoing.

There is a world of devoted women in Naples. They are devoted to culture, wisdom, good social practices, solidarity without chatter and grand announcments, and often expressed spontaneously. But, men too participate, like Peppino Sansone, a newsagent and bookseller in the Chiaia district, who brought medicines and newspapers to all his customers and, on Palm Sunday, took a blessed olive branch to the door of those who hadn’t even expected it.

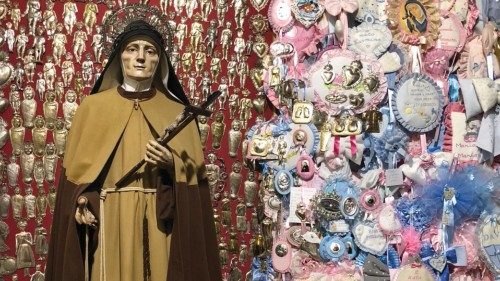

Those who come to the city for the first time discover an ancient tradition, dating back to the terrible plague of 1656. when the city was reduced by two thirds in six months and people died in the streets, with figures of as many as twenty thousand a day. Those arriving, discover that the Neapolitans worship anonymous skulls in the cemetery of the Fontanelle, a giant ossuary built in one of the tuff quarries as high as cathedrals that has made Naples, since the time of the Greeks, a city of sea and light on the surface, and caverns, pools and aqueducts underground.

To the “capuzzelle”, or skulls renamed with a name, and to which stories are invented and powers are attributed (skulls that sweat, skulls that belong to ship captains, skulls of dead people who, if offended, return to take revenge, skulls of young brides to ask for the grace of a pregnancy or a happy marriage). The Neapolitans have been devoted for long centuries to the "capuzzelle". During the plague in the seventeenth century, thousands of people hid the bodies of the dead under the streets, they calcified mass graves with the words “tempore pestis: non aperiatur”. The neapolitans handed over relatives in agony to the “seggiari”, the gravediggers recruited among the prisoners who took away not only the corpses, but also the living.

Then, on a day in August, after a great downpour, the dead came out of the “Chiavicone”, the great sewer that runs under the city; and palaces also fell. The devotion for the dead began that year, or rather, took a special form, which was a consequence of enormous pain, a sense of guilt; the guilt of having remained alive.

Never before has devotion for the living been more necessary than today.

A devotion for life, which is made up of meals and caring, but also and above all, culture: women in Naples know it, they have always known it. And they have not forgetten it.

by Antonella Cilento

The author

Born in Naples in 1970. Finalist in the Premio Strega literary prize in 2014 with Lisario o il piacere infinito delle donne (Mondadori), she has published numerous novels, collections of short stories, and historical reportages. Since 1993 she has directed one of the oldest Italian writing schools, “Lalineascritta Laboratori di Scrittura” (www.lalineascritta.it) and coordinates the first master’s degree in writing and publishing in Southern Italy, Sema, with Suor Orsola Benincasa University. She has directed the international literature review Strange couples for twelve years. She writes for the theater and La Repubblica - Naples.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti