Where is the other half of the Church? This is the question Cardinal Léon-Joseph Suenens, Archbishop of Malines-Brussels asked as he addressed the 2,500 Council Fathers, and with it the request for a female presence was formulated. The question was then repeated by other bishops, and so desired by the lay auditors present during the second session of the Second Vatican Council. This was the signal of a germinal awareness that made one perceive how very serious the absence from the Council chamber of those who make up half of humankind actually was. On September 14, 1964, at the beginning of the third session of Vatican II, Paul VI addressed the 23 admitted female auditors, 10 religious and 13 lay women with the following words: “We are pleased to greet our beloved daughters in Christ, the women auditors, admitted for the first time to attend the Council assemblies”. None of the nominees were present. On September 21, the first to enter the Council chamber was the French laywoman Marie-Louise Monnet, founder of Action catholique des milieux indépendants. The best known amongst them were the Australian, Rosemary Goldie, executive secretary of the Standing Committee of International Congresses for the lay apostolate, and the Italian Alda Miceli, president of the Italian Women’s Centre. They were joined by about twenty experts including the economist Barbara Ward and pacifist Eileen Egan.

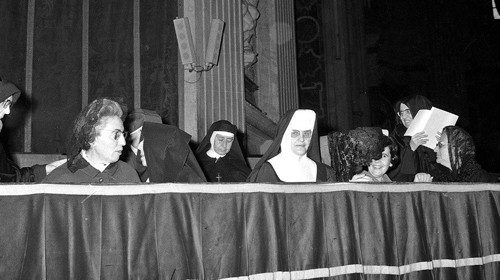

Women were chosen to represent or coordinate lay organizations that were often active at an international level, and others who were general superiors of religious institutes; none of them had systematic theological studies as part of their academic preparation. The “Mothers of the Council”, as they were called, attended meetings dressed in black (except for one) with a veil covering their head, as if they were attending a pontifical function. During the intervals, they could go to a separate room-bar, which had been prepared for them. Pilar Bellosillo, president of the World Union of Catholic Women’s Organizations, was denied twice the opportunity to speak in public. They had neither the right to speak nor the right to vote. The participation of the female auditors, as per the intentions of the Council Fathers, had to have a rather “symbolic” character, as Paul VI himself indicated in his speech in which he reported the appointment and greeted their presence. In reality, they were anything but symbolic, participating with determination and competence in the work of the commissions. Although limited to the last two sessions of the Council -the third (14 September - 21 November 1964) and the fourth (14 September - 8 December 1965)-, their presence, as has been noted more recently, was particularly lively and significant. They left important signs in the Council documents themselves, and presented memoirs and contributions of their experience to the drafting of the documents, particularly on topics such as religious life, the family, and the lay apostolate. The presence of two war widows also helped to strengthen the weight of women in the discussions on peace. The contribution of the economist Barbara Ward to the debate on the presence of the Church in the world and her commitment to the Church to say a credible word on the problem of poverty and human development should also be underlined.

On November 23, 1965, the thirteen female lay auditors, together with their male counterparts published a joint declaration to account for the work that had been done. Aware of having witnessed a historic stage in the opening of the Church to its lay component, they stressed the vital importance of some documents to which they had made a significant contribution through discussions and exchanges of ideas.

In particular they referred to Chapter IV of Lumen Gentium, dedicated to the laity, the parts of Gaudium et Spes concerning the participation of the faithful in the construction of the human city and the decree on the apostolate of the laity Apostolicam Actuositatem. Thanks also to them, the Council had therefore dealt with issues such as the building of peace, the drama of poverty in the world, the need of overcoming inequalities and injustices, the defense of freedom of conscience, the values of marriage and the family, the unity of all Christians, all believers and all humanity. The contribution of the lay auditors was particularly significant within the commissions charged with drafting the decree on the apostolate of the laity and the text of what was called “Schema XIII”, which later became the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the contemporary world, Gaudium et spes.

The influence of the female auditors was therefore mainly on two documents on which they had worked from within the subcommittees. These include, the constitutions Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes, in which the unitary vision of man-woman as a “human person” and the fundamental equality of the two emerged. A moment in the proceedings, which was very significant, was Rosemary Goldie’s answer she gave to the theologian Yves Congar, when the famous Dominican wanted to include in the document on the Apostolate of the laity an elegant expression, comparing women to the delicacy of flowers and the rays of the sun: “Father - he said - leave the flowers out. What women want from the Church is to be recognized as fully human persons”.

We know of the authoritative interventions of some of the women present (Rosemary Goldie, Pilar Bellosillo and Suzanne Guillemin) so that the affirmation of the dignity of the human person would go beyond any specific consideration of the issue of femininity, which was not treated as an issue in isolation, separated, but freed, from any cage and limitation. In particular, their interventions included the recovery of baptismal subjectivity. The primacy of fundamental equality, conferred by baptism on believers, gives everyone, men and women, the principle of apostolic co-responsibility.

The laity, both women and men, are therefore no longer relegated to passivity and receptivity; instead, by virtue of baptism, they receive an active and important role in the Church. To understand, on this point, the state of affairs in the Church is enough the letter that the future John Paul I, then Bishop of Vittorio Veneto, is quite sufficient. He had sent the letter to the Assistants of the Union of Women and Women’s Youth of the Catholic Action, who, commenting on the appointment of female auditors, wrote this way: “No one will have a plunge to the heart, as an acquaintance of mine, when the other day he read in the newspaper that Rosemary Goldie, as an ‘auditor’ at the Council, had become a ‘speaker’, expressing in front of a group of bishops some reservations about the Scheme of the laity, hoping it would be less paternalistic, less clerical and less juridical. ‘It will end up - the parish priest concluded astonished - that because of these good daughters, the Catholic Action will no longer be the collaboration of the laity in the apostolate of the hierarchy, but the collaboration of the hierarchy in the apostolate of the laity!’ You see, the laity - I said - judge certain clericalism as an exaggeration, the fact that everything, absolutely everything, in the Church must start from bishops and priests”.

The contribution of the auditors was also of great importance in overcoming the traditional contractual and legal concept of the family institution, through the recovery of the fundamental value of conjugal love, based on an “intimate community of life and love”. In this perspective, the contribution of the Mexican Luz Marie Alvarez Icaza, co-president of the Movimiento Familiar Cristiano, in the subcommittee of Gaudium et Spes was decisive in changing the bishops’ attitude towards sex in the married couple, to be considered no longer as a “remedy for concupiscence” linked to sin, but as an expression and act of love. Luz Marie Alvarez Icaza, very active within the group that was to examine the “Schema XIII”, questioned what the theology manuals, in use before the Council, defined as “primary ends” and “secondary ends” of marriage, where primary was the procreation of children and secondary was the remedy for the concupiscence of the sexual act. To a Council father she replied: “It is very disturbing for us mothers of families that our children are the fruit of concupiscence. Personally, I have had many children without any concupiscence; they are the fruit of love”.

.It is therefore possible to grasp an initial maturation of awareness of the contribution made by women to the life of the world and the Church. Particularly enlightening in this regard is what is said in Gaudium et spes 60: “Women now work in almost all spheres. It is fitting that they are able to assume their proper role in accordance with their own nature. It will belong to all to acknowledge and favor the proper and necessary participation of women in the cultural life”. However, these fundamentals are still struggling to develop and mature today. The study of the texts produced and the speeches of the Fathers made it possible to perceive how limited was the awareness of the transformations that were already taking place in the world of women, whose entry into public life John XXIII had indicated in Pacem in Terris as a “sign of the times”. At the same time, however, that Vatican II offered women new perspectives of recognition of identity and ministry cannot be disregarded. In particular, in the recovery of baptismal subjectivity (as stated in Lumen gentium and Gaudium et spes), new spaces have been opened for the presence of women in ecclesial life. In addition, new forms of de facto ministries, renewal of religious life, entry into the Theological Faculties as learners and lecturers have progressively changed the face of the local Churches, on different continents, and fostered the maturation of new sensibilities. In this direction, the Council has activated a change with no return. Moreover, certainly one of the fundamental steps for women has been access to theological studies. This means that the history of the Church has begun to be told also by women, who interpret and narrate it.

By Stefania Falasca

The women who accomplished the feat

Religious women auditors: Mary Luke Tobin (USA), Marie de la Croix Khouzam (Egypt), Marie Henriette Ghanem (Lebanon), Sabin de Valon (France), Juliana Thomas (Germany), Suzanne Guillemin (France), Cristina Estrada (Spain), Costantina Baldinucci (Italy), Claudia Fiddish (USA), Jerome M. Chimy (Canada).

Lay women auditors: Pilar Belosillo (Spain), Rosemary Goldie (Australia), Marie-Louise Monnet (France), Amalia Dematteis widow Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo (Italy), Ida Marenghi Miceli widow Grillo (Italy), Alda Miceli (Italy), Luz Marìa Lngoria with her husband José Alvarez Icaza Manero (Mexico, mother to 13 children), Margarita Moyano Llerena (Argentina), Gertrud Ehrle (Germany), Hedwing von Skoda (Czechoslovakia-Switzerland), Catherine McCarty (USA), Anne Marie Roeloffzen (Netherlands), Gladys Parentelli (Uruguay).

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti