The title of Pope Francis' third encyclical, with its incipit “Fratelli tutti”, sparks strong reactions in some quarters. In fact, Francis of Assisi, who is quoted here, addresses all believers and all people – brothers and sisters in the entire world. The following article identifies the source of the name of the new encyclical and calls for accurate translation.

Weeks before Pope Francis' third encyclical will be signed in Assisi and its text (1) published, a debate over its title has already been triggered. In some German and English-speaking areas, for example, there are women who are set not to read a written work that is addressed only to “fratelli tutti”. Translations with little sensitivity ignore the fact that in the cited work, Francis of Assisi is addressing both women and men. The medieval author endorses, as does the new encyclical, universal fraternity. Pope Francis highlights a spiritual pearl of the Middle Ages capable of surprising modern readers, both male and female.

A quotation of Brother Francis

When the encyclical was announced, various media rightly wondered if Pope Francis had placed a discriminatory quotation at the beginning of his third encyclical. How is it possible that he, whose first public words after his election were “brothers and sisters”, would now address only “fratelli tutti”? Why does the incipit – the first few words of a text that also serve as its title - exclude women and thus exclude half the Church? “Only brothers – or what?”, asks a critical article by Roland Juchem (2). The director of the Vatican service of KNA (Catholic News Agency) explains that the new encyclical consciously begins with the words of the Medieval mystic of Assisi, which were translated faithfully. Since Brother Francis is addressing his brothers, the expression “omnes fratres” should be formulated in the masculine. According to this logic, however, the correct translation would be “Frati tutti” [“Friars all”]! And so the text would be read only by an infinitesimal minority in the Church. Pope Francis begins his new encyclical with a maxim of wisdom authored by his model. Those who, with presumed faithfulness to the text, insist on a translation only in the masculine, do not recognize the true addressee of the medieval collection. Francis of Assisi, with the final composition of his text, addresses all Christian men and women. Translations into modern languages must express it in an accurate and immediately comprehensible way.

Collection of wisdom sayings

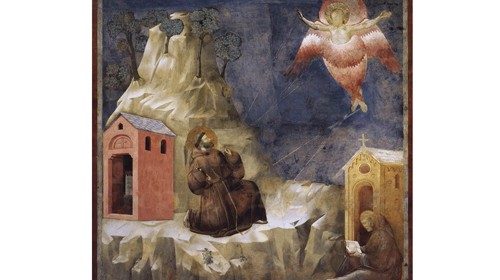

Just as the opening words of the encyclical Laudato Si' quoted the Canticle of Brother Sun, Sister Moon, composed by the Poverello of Assisi in the old Umbrian language, the Pope's third encyclical refers to a collection of his maxims of wisdom. The main source used by Pope Francis in Franciscan writings bears the title Admonitiones. The expression “admonitions” is too limited, because the full set of 28 spiritual teachings also includes numerous beatitudes, a brief essay and even a canticle about the strength of the gifts of the Spirit (3). The Dutch edition in fact prefers to speak of “Wijsheidsspreuken” (maxims of wisdom) (4). The fact that they are addressed to ‘brothers’ is true only for some individual maxims, not for the entire collection. When translators rely on the fact that all standard editions of Franciscan writings in all the languages of the world translate the omnes fratres of the cited maxim into the masculine form, they err in judgment, and thus understand only a half truth. In other words, the literal translation of the Latin sentence does not reflect the full meaning that the text intends to express in its final form! In the Italian/German edition of Franciscan Sources, the sixth admonition begins with the words: “Let all of us, brothers, consider the Good Shepherd Who bore the suffering of the cross to save His sheep” (5). Here one can already note that the image of the shepherd and his flock used in the text includes the entire Church, and not just a multitude of friars or monks. To recognize the final addressee of the collection of texts cited by the Pope, it is necessary to distinguish between the genesis of the various parts of the text and their final compilation. In the latter, the word fratres is expanded from the small circle of Franciscan initiates to all people.

From the puzzle piece to the complete picture

The quoted locution comes from a collection that gathers spiritual discussions among the brothers and the considered conclusions of those discussions. The overall skilful collection expands the horizon beyond the small initial circle.

The individual maxims are addressed to Francis's friars, to “religious” people in general and also to all people at the service of God (servi Dei). In the last years of his life, Francis of Assisi put together 28 well selected spiritual teachings to form a series of lessons that construct a spiritual edifice and recall the biblical “house of Wisdom” with its “carved pillars” (6). The symbolic number 28 is composed of 4 times 7: the four indicates the world and the seven God's creation; the 28 symbolically represents the universal Church as a work of God (7). Who enters under an artistically adorned portico and limits him or herself to looking at only one pillar? All people, without exception, are invited into this spiritual edifice, and in fact the individual passages in the collection are addressed to everyone.

Omnes fratres

The first admonitio speaks specifically of questions regarding the Eucharist, but intentionally also addresses all people (8). Hence, the Latin text in the inviting incipit clearly indicates that the horizon of hope is open to all the daughters and “sons of man”. On their way through the house of Wisdom, they will discover a path towards a “life that makes one happy” (9). In fact, at the centre of this series of spiritual lessons, Francis of Assisi interprets biblical beatitudes, which are also addressed to all people, adding ten beatitudes of his own. Pope Francis does not highlight a single text, but rather a collection of texts that Kajetan Esser defined as the Magna Carta of Christian fraternity (10). The subtitle of the encyclical makes it obvious that it is addressed, like the Christian-Islamic joint document of Abu Dhabi “on human fraternity”, beyond one’s own Church, to humanity. Pope Francis writes “on fraternity and social friendship”, which must unite, without any exclusion, all the people in a supportive world.

From “frati” to “brothers and sisters”

What justifies Pope Francis, with his fraternal vision of humanity, referring to Francis of Assisi as his model and placing a fraternal quotation at the beginning of his encyclical? Consider this brief explanation. The preserved writings of the Saint contain a collection of letters, some of which are addressed to individual brothers (Leo, Anthony, government leaders) while others are addressed to the entire confraternity and to all the faithful. But there is also one circular letter that extends the horizon to the universal and is addressed “to all mayors and consuls, magistrates and governors throughout the world and to all others to whom these words may come” (11). No pope and no emperor of the Early Middle Ages addressed all of humanity in such a universal way. In the Rule of 1221, which is presumably addressed only to his brothers, Francis includes an invitation that extends beyond every border of nation and religion: not just Christian faithful and not just the people committed within ecclesial structures, but rather “all peoples, races, tribes and tongues, all nations and all peoples everywhere on earth, ... let us all love the Lord God” (12). The mystic expands his own horizons to the entire human family even in the Rule specific to friars, a few months after arriving in Egypt in the fifth Crusade and having felt in a striking manner, through his encounter with Islam, that it is possible to find spiritual wisdom and the love of God even outside one's own religion (13). The same universal opening also occurs with his maxims of wisdom, which in the Admonitiones are skillfully united in a series of lessons. In the last years of his life, Francis includes what had been words of wisdom to his brothers in a complete composition that addresses all the faithful. The Latin text requires no addition: the expression “fratres” used for the religious includes also sisters, as still today do “fratelli”, “hermanos” and “frères” in Latin languages which do not have a term for parallel usage regarding the female gender. Today, the German language makes a distinction between “Brüder” or “Gebrüder” and “Geschwister” and also between “Brüderlichkeit” (without sisters) and “Geschwisterlichkeit” (with sisters). Similarly, English distinguishes between “brothers” (purely masculine) and “siblings” (brothers and sisters), and between “brotherhood” (often without sisters) and “fraternity” or “siblinghood” (everyone included).

Later, after the first admonition allowed all “sons and daughters of man” to enter the beautiful house of Wisdom, this universal form of address also begins the sixth admonitio with reference to fratres, for it addresses all Christian women and men and calls out to all people on earth.

On the origin of the quoted source

With regard to the collection of 28 maxims of wisdom, Franciscan research affirms that the individual preserved texts summarized longer discourses about the spiritual and communal life of the friars. In the course of time, some ideas were summarized in writing and highlighted. Thus something analogous occurred to what happened with the sayings of the ancient fathers and mothers of the desert in the circles of their followers, preserved in a condensed fashion in the Apophthegmata and in the Meterikon (14). The individual teachings of Francis were also written down in diverse situations by people capable of writing, and were summarized in their essence. Toward the end of his life, he himself combined these results of communal discourses; once collected into a complete work, the individual teachings acquired a new dimension.

It is no coincidence that the first teaching begins with a scriptural quotation that sets the theme: “The Lord Jesus said to His disciples: 'I am the Way, and the Truth, and the Life'”. The Romanesque entrances of churches sometimes invite one to enter the building with a figure of Christ in the tympanum, and precisely this same quotation in an open book. In the spiritual edifice of the Admonitiones, two preparatory teachings lead to ten maxims of wisdom that outline the “way of truth”. Following them are four biblical beatitudes and another ten Franciscan beatitudes, before two concluding teachings prepare for the return to daily life. The individual teachings are combined in this way in order to create a spiritual house of wisdom that resembles a basilica: on the left of the nave twelve pillars lead, as the “way of truth”, toward the area of the altar, whose canopy is supported by four slender pillars, and identify the place of intimate communion with God. Then, on the other side of the nave, twelve pillars lead back to the entrance and indicate the “way of life”. Via – veritas – vita are the keys of the composition of a complete work whose individual passages, even separated from the context in which they were born, are a message for all Christians, men and women

Whoever may be interested in the collection of the texts from which Pope Francis draws the incipit of his encyclical will soon find an analysis of the composition and the complete message in a specialized series of the Philosophical-Theological University (PTH) Münster (15).

Conclusion

With the incipit of his third encyclical, Pope Francis expressly refers to Francis of Assisi. In the Canticle of Brother Sun, Sister Moon, the saint’s universal fraternity extends to all people and all creatures. Among the saint's circular letters there is one that addresses all the people on earth in a universal fashion. Even in the Rule of the Order of 1221, composed for Franciscan friars, he addresses all persons and all peoples with an invitation. The sixth admonitio quoted by the Pope condenses the results of a spiritual discourse in the sphere of the Brothers Minor; that is the context in which it was born. The spiritual teaching that inspires the incipit of the new encyclical, however, was included by Francis toward the end of his life as a pillar in the “house of wisdom”, where the capitals form images that mirror each other. Not only brothers, but all believers and every person on earth are invited to traverse this spiritual edifice. Thus the “omnes fratres” or “fratelli tutti” of the encyclical is to be translated as a quotation of Saint Francis so that all Christians, men and women, feel involved. The addressees of the quoted collection of texts comprise “all the brothers and sisters” who meet in real and ideal ecclesial spaces, and by extension, all human beings on earth. Likewise Pope Francis, with this incipit, addresses his encyclical to all human beings on earth.

by Dr. Niklaus Kuster

Niklaus Kuster (1962) is a Swiss Capuchin friar with a degree in theology and a noted scholar of Saint Francis. He teaches Church history at the University of Lucerne and Franciscan spirituality in the Order's superior institutes in Münster (PTH) and Madrid (ESEF). He paid tribute to Pope Francis's Franciscan profile in his book Franz von Assisi. Freiheit und Geschwisterlichkeit in der Kirche, (Verlag Echter) Würzburg 2 2019.

Notes:

(1) The encyclical will be signed very symbolically on the eve of the Feast of Saint Francis, 3 October 2020, in the basilica of the Saint in Assisi.

(2) The article was published online on 8 September 2020: “Titel der neuen Papst-Enzyklika: Nur die Brüder – oder wie?”: https://www.kath.ch/newsd/titel-der-neuen-papst-enzyklika-nur-die-brueder-oder-wie/

(3) Francis of Assisi, Early Documents. vol. I: The Saint, ed. by Regis J. Armstrong, J. A. Wayne Hellmann, William J. Short, New York - London - Manila 1999, 128-137.

(4) Gerard Pieter Freeman /Hubert J. Bisschops / Beatrijs Corveleyn /Jan Hoeberichts / André Jansen (ed.), Franciscus van Assisi. De Geschriften, Haarlem 2004, 108–122.

(5) Early Documents I, 131.

(6) Proverbs 9:1: “Wisdom has built her house, she has set up her seven pillars”; cfr. Proverbs 14, 1 e 24, 3-4.

(7) On the symbolism of the Admonitiones as an ideal church open to all: Theo Zweerman / Edith van den Goorbergh, Franz von Assisi – gelebtes Evangelium. Die Spiritualität des Heiligen für heute, Kevelaer 2009, 69-71.

(8) Admonitio I:14 with Psalm 4:3 in the version of the Vulgate: “filii hominum”.

(9) The collection of the admonitions as subtly composed pathway of teaching and spiritual edifice is explained by Zweerman / Van den Goorbergh, Gelebtes Evangelium, 62–94.

(10) Cf. Niklaus Kuster, Franziskus. Rebell und Heiliger, Freiburg 42016, 150–154; originale: Kajetan Esser, Anfänge und ursprüngliche Zielsetzungen des Ordens der Minderbrüder, Leiden 1966, 273–276.

(11) Early Documents I, 58.

(12) Early Documents I, 84.

(13) Cf. Niklaus Kuster, Spiegel des Lichts. Franz von Assisi – Prophet der Weltreligionen (Franziskanische Akzente 22), Würzburg 2019.

(14) Los escritos de Francisco y Clara de Asís. Textos y apuntes de lectura, ed. by Julio Herranz – Javier Garrido – José Antonio Guerra , Oñati 2001, 40; Pietro Messa – Ludovico Profili, Il Cantico della fraternità. Le ammonizioni di frate Francesco d’Assisi, Assisi 2003; Francisci Assisiensis Scripta – Francesco d’Assisi: Scritti, critice edidit Carolus Paolazzi, Grottaferrata 2009, 346.

(15) Niklaus Kuster, Weisheitssprüche des Franz von Assisi. Zum Charakter der Admonitiones und zur Komposition ihrer Sammlung“, in: Möllenbeck, Thomas / Schulte, Ludger (ed.), Weisheit - Spiritualität für den Menschen, Münster 2021 (to be published in the spring).

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti